BERET is another in my “Hat” series – a line of powerboats that, for some unfathomable reason, are all named after hats. They have hard-chine hulls and, for ease of construction, are generally planked with sheet plywood. They are of the semi-displacement type, designed to use modern outboards for power, although most of them can be modified for inboard diesel propulsion. The series can trace its genome back to Harry Bryan’s inspired little Handy Billy design, and thence back to William Hand, who in the early 1900s pioneered the concept of chine-type hulls for powerboats.

I think that the semi-displacement hull form is the real sweet spot in the powerboat continuum. They popped up amazingly early in powerboat history, soon after people discovered that true displacement hull speed could indeed be defied and that, with more power, boats could be pushed at speeds beyond the classic 1.3 times the square root of their waterline length. They are most famously represented by the early Maine lobsterboats, but many Chesapeake deadrise boats would also qualify. Either of those as 36-footers, instead of topping out at a theoretical 1.3 x 6 = 7.8 knots, could do an easy 12. With rediculously big engines, both types have been pushed to plane at well over twice that speed in recent years, proving that, with sufficient applications of fossil fuels, anything can be made to go faster than it should.

The beauty of the semi-displacement type is that it can exceed hull speed but still operate perfectly well if slowed down to the displacement range. A true displacement hull will be slightly more efficient below hull speed, but as hull speed is approached, a good semi-displacement hull will be more efficient. It can then go on to about 2.5 times hull speed, with decreasing but still reasonable efficiency. These boats will handle beautifully at speeds between where a displacement boat is battling its bow wave and a planing boat is struggling to get out of it’s hole.

BERET is another of my “imaginary designs” which means that the plans are developed only enough to assure that the basic ideas will work, but I have not invested the serious time it takes to produce a set of working drawings. Like a young child’s “imaginary friend,” these designs have pretty much what I would want for my own purposes. So read on, and I’ll give you a short tour.

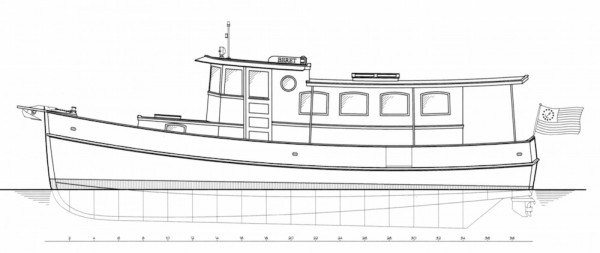

Now that my wife, Jean, and I are approaching some semblance of retirement, and Maine winters have lost some of their luster, thoughts are turning towards warm water cruising. BERET is aimed at roughly the same type of cruising as my last imaginary design, TUVA II, but is sized more for a couple than for a family. She would be “low impact” not just on the environment, but hopefully on her owner’s wallet as well, designed to run at a slightly more leisurely pace, and to be most comfortable in protected waters. Her hull is shallow and wide, much of it used for tankage, systems, and storage of the myriad junk that a life afloat seems to accumulate. Low freeboard allows easy boarding from dinghy or dock, and high bulwarks help keep grandparents and grandchildren onboard. Most of the accommodations are up on deck, making for grand viewing of the scenery, whether at anchor or underway.

The so-called trawler or tug configuration means that the pilothouse is high and placed well forward. This is not its best location for a good sea boat; in rough weather, everyone would be happier to be lower down and further aft, as in TUVA II, where there is less motion. On the plus side, there is a better view (more scenery, less foredeck) and easier docking and anchoring. On a questionable day, when TUVA II’s crew might vote for a fast dash “outside,” BERET’s skipper will likely opt to run inside on the waterway at a more moderate speed.

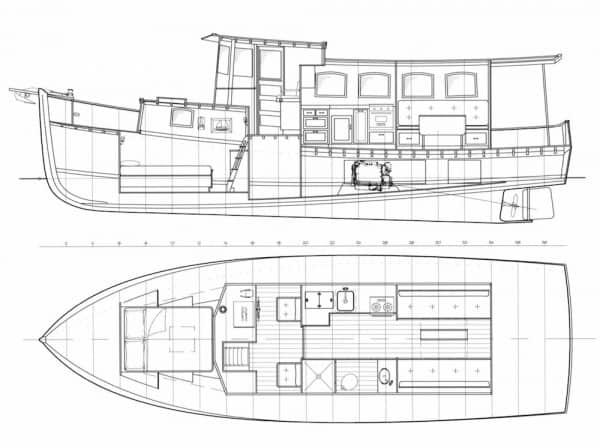

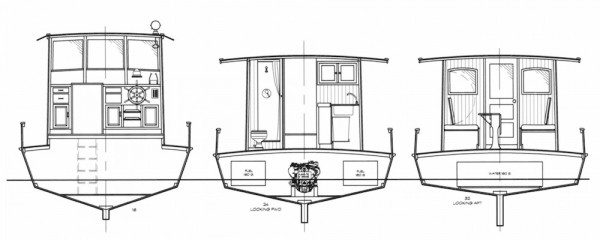

The drawings will likely be enough to explain most of the rest of BERET’s accommodations. Starting up forward, an honest-to-gosh double bed dominates the fo’c’s’le, and WalMart’s fitted sheets will work on it just fine. This is a real “master bedroom,” with space for all the clothing and linens required for long-term cruising. Face aft and climb the companionway ladder and you will enter the pilothouse with its large “dashboard” for spreading out charts, mugs of coffee and any meals you choose to take while underway. There are comfy seats for the captain and first mate and sliding doors port and starboard— handy for stepping out to handle lines or take videos of those dolphins playing in the bow wave.

Continuing aft, you step down to the main deck level where there is a spacious galley to starboard and a toilet room with separate shower to port. A few steps further aft brings you to the saloon. I’m a firm believer that many of the best times in cruising take place around a big drop-leaf table where a crowd can sit down to a convivial dinner and swap yarns. A symmetrical arrangement is more restful to the eye and brain, and that’s what we have here. The settee backs swing up to block off the side windows and expose generous berths when the saloon is used for bunking down the occasional overnight guests.

Slowing down is the primary way to give any boat a “low impact” status, but there are other aspects as well. To my mind, a gen-set increases the impact of any vessel: to the environment, to the pocket book, and to anyone anchored close by. Gen-sets must be about the most expensive way there is to create a kilowatt of electricity when the costs of purchase, installation, and maintenance are all added up. And to boot, they destroy the peace of idyllic anchorages, even if they’re equipped with the best mufflers money can buy. They are used mostly for servicing electric ranges; the most absurd of all marine appliances, but with air conditioning probably a close second.

You can easily forgo a gen-set and still enjoy all the conveniences it provides. A fuel cookstove is the first step. Natural gas, propane, butane, alcohol or diesel will all do the job. Next is a big battery bank and an inverter/charger to match. For charging, you will want either an oversize alternator on the propulsion engine, or a generous solar array, or both. All this may weigh a bit more than a gen-set, but it will cost far less. Fortunately, recent advances in lighting and refrigeration technology have made it possible to enjoy both of these comforts with minimal battery drain.

It wasn’t that long ago that we managed without air conditioning, so it’s worth looking at some old techniques for keeping cool. Everyone knows that using light-colored paint, and incorporating lots of ventilation is a must. BERET’s overhanging boat deck helps further by shading much of the cabin beneath it during the heat of the day, as well as making it possible to leave the side windows open during most rain showers.

I have shown both an inboard diesel and twin outboards for powering BERET. Each has its advantages. Twin outboards offer the gift of very quiet operation as well as low initial cost; they also offer simple and fast replacement, enhanced maneuverability, reduced draft, and increased reliability by virtue of their redundancy. An inboard diesel, however, can generate domestic hot water and drive an oversize generator. The theoretically-lower operating cost of a diesel is offset by its high initial cost, and the fact that diesel fuel now sells at a premium. The longevity and reliability of outboard motors increase with each model year, while modern lightweight, high-rpm diesels are losing ground on this front.

BERET’s hull is designed for plywood construction, using two layers of 1/2” material. This type of construction is fast and easy for the amateur builder, and makes it possible to use a non-developable bottom panel shape. Fiberglass or Dynel sheathing will reduce maintenance and make her immune to ship worms. The inherent stability of the beamy, chine-type hull will offset the height and weight of her superstructure, and her shallow draft will open lots of secluded anchorages that are off limits to deeper boats. With twin 60 hp outboard motors, she should have a top speed of about 12 knots, and cruise comfortably at 10. At eight knots, she will consume only about 3.5 gallons per hour.

Doug Hylan

Bruce MacNeil says:

Doug, I sincerely admire your designs and style, they are beautiful and very traditional. On another note I am restoring the windshield on an Able 34 built in 1995. We have a three window windshield and want to add a opening window in the center. Do you have any suggestions for a mahogany opening window design that does not leak. We imagine a hinge at the top and bottom opening as one option. any thoughts.

Thank you for your thoughts, Bruce.

David Tew says:

Oh, goodness. How did I miss this?! I fantasize of a partnership with two or more other couples each taking six weeks of winter in southern climes in respite from Maine winters.

Christopher Chadbourne says:

Doug,

I like Beret… and the design philosophy she represents.

I’m glad that someone is finally making the point about using modern outboards for main propulsion. If you cruise at speed length ratios of 1 to 1.2, it’s surprising how economically even an (ahem) portly hull form can be pushed along. They might be the modern equivalent of all those Chrysler crown gas engines that used to power West Coast troller fishboats.

But it’s also surprising how a short steep chop can make a cruiser like Beret pitch. Would you please comment on the availability and use of long shaft outboards to get those props further down into the water?

By the way… in the late 1960’s Charlie Wittholz drew a series of tug cruisers much like Beret. They were for clients of moderate means, and so tended to be built in small commercial yards like Carl Rice’s yard in Reedville Virginia. Good oak and long leaf yellow pine were the order of the day, and tasteful paint set off their solid construction and simple joiner work.

Chris

Doug Hylan says:

Hi Chris,

As you perceive, Charles Wittholz’s trawler series was part of the inspiration for BERET. And, I will agree that there are times when those props could ventilate in a severe chop. On the drawings, the props are set for semi-displacement speeds, with the anti-cavitation plates at the bottom of the hull. At higher speeds, I think the hull would squat enough to keep the props in good water.

If you were intending to mostly run below hull speed, it might be better to set the props lower. There would be a slight increase in drag due to the extra amount of lower leg projecting below the hull, but that would be negligible at the speeds you mention.

Motor manufacturers have come out with extra-extra long shaft motors, thanks to the current trend of trying to fit more and more motors on the sterns of deep vee hulls. These are mostly only available in the upper horsepower ranges, but even the Yamaha mid range motors are available with 25″ legs. So, I think there is the opportunity to address your concern by using these motors and setting the props lower.

Many years ago, I did some cruising in a Frank Day lobster boat with a Chrysler Crown engine. Even with the most rudimentary of engine boxes, that boat was quieter than a diesel with a thousand bucks worth of sound proofing!

Thanks for your insightful comments, Doug Hylan

Gregory Phillips says:

Vey nice in all respects, Doug.

Greg Phillips

Brooklin

Apalachicola

Randy Pickelmann says:

Hi Doug!

Nice boat!

As a long-time live aboard trawler driver and a long-time Florida resident, I have two thoughts.

First, by using outboards, you remove a significant heat source from inside the hull to outside. At the end of the day, after shutdown, our diesel continues to heat the boat through the evening…whether we want it or not.

Second, don’t be too quick to dismiss air conditioning. If you are planning to spend time in Florida, especially in a marina, air conditioning greatly enhances Mom’s comfort. As we all know, if Mom ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy! When you are at anchor or on a mooring and there is plenty of breeze, no problem. But in a marina where you aren’t able to lay head to the wind it gets miserable pretty quick. I’ve seen what happens to you Maine boys when the thermometer climbs above 90 degrees!

Christopher Chadbourne says:

Randy,

I couldn’t agree more about the comfort price you pay for a marine berth in a hot climate. For years my boats swung on a mooring on the Chesapeake Bay; we loved it, summer included. When we moved our motor cruiser to a berth at the head of the T pier we really noticed the difference.

Notwithstanding, I propose two complementary old-time alternatives to air conditioning for Beret. First, A proper anchoring/mooring system should always be paired with a proper dinghy and dinghy access. How about davits and a transom door for Beret? (Saves the cabin house top for solar panels…) Second, I’m sad to see the demise of wind scoops and awnings, especially on power cruisers. For instance, a wind scoop on Beret’s forward hatch combined with a foredeck awning (to shield the pilothouse windows) and side curtains (to block the afternoon setting sun would help a great deal.

Chris

Bill Mayher says:

Doug,

You have pretty much nailed the design we have been talking about since the early fall: the whole tug trawler thing, ventilation and views, good seating in the main saloon, relative simplicity (especially if one takes up the outboard motor option), attention to shippy details. Nice going.

Bill