Here’s the next batch of photos from our National Fisherman collection. Remember you can see the entire collection here. We have around 100,000 images viewable online, any of which can be ordered by contacting me. I hope you enjoy the photos that follow, and learn from them. —Kevin Johnson, Photo Archivist, Penobscot Marine Museum.

The Thinker. The 77-foot Seattle-based fishing vessel WESTWARD of 1918 is about to get a new stem and the other timbers that go with it—and this takes heavy thinking beforehand. (LB2012.15.3270)

The Planners. Forefoot timbers are in, the rabbet has been cut, and WESTWARD is ready for the new stem itself. Frames and planking will follow. (LB2012.15.3274)

The Doer. Happy at his work, and with mallet and chisel in hand, this guy is cutting the rabbet in WESTWARD’s new stem that will receive the planking. (LB2012.15.3273)

The Planking Gang. With WESTWARD’s new stem and forefoot timbers installed and three new frames attached to them, the crew now drives the spikes that attach the planking. (LB2012.15.3272)

Over She Goes. Chesapeake Bay deadrise boats, both power and sail, start life upside down. After their bottoms have been planked and their topside planking begun, they’re turned rightside up for completion. (LB2012.15.4001 from a May issue of National Fisherman, p. 17-C)

Boatbuilding By Rack of Eye. Boatbuilder Joseph Lolley of Eastpoint, FL, sets up a new 35-foot hull, using an old method of bending longitudinal battens around a midship frame, adjusting them to suit his eye, then obtaining the shapes of the remaining frames from the battens. Those frames are then sawn out, pieced together, and erected. (LB2012.15.3287 from National Fisherman, May, 1979, page 84)

Boatbuilding By Detailed Drawings. Boatbuilders Art Wester and Art Brendze (Traditional Marine Service of Arundel, ME) examine the plans for the 24′ Fenwick Williams-designed yawl they’re building—which will be launched as ANNIE. (LB2012.15.3308 from National Fisherman, October, 1978, page 72. Photo by Hanson Carroll)

Yacht Building at Hinckley’s. Before shifting to fiberglass in the early 1960s, this Southwest Harbor, Maine, yard, used to build its stock sailboats of wood. Those were the days of the Hinckley Sou’wester and the Hinckley 36 as well as the Hinckley-built Pilots and Owens Cutters. (LB2012.15.3322. Photo by W.H. Ballard)

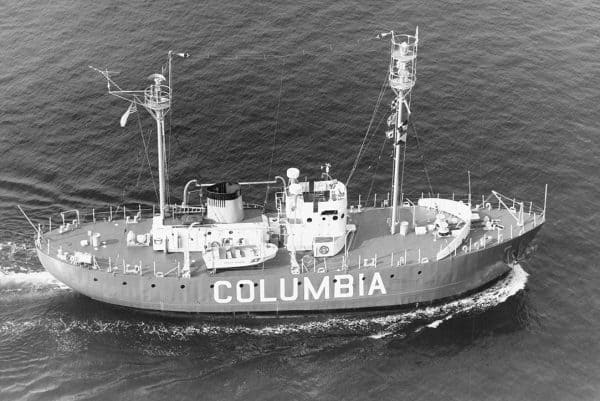

Dragger Building at Wallace’s. R.L. Wallace & Sons, the short-lived successor to Newbert & Wallace, continued the hull numbering that N&W began back in 1941. COLUMBIA was #98 and the last built at this Thomaston, Maine, yard and the last of her breed anywhere, since by 1985 steel stern trawlers had taken the place of eastern-rigged vessels like this one. Owner, Myron Marder of New Bedford (Marder Brands, Inc.) died in 2012 at age 91 and the 32-year-old COLUMBIA, sold earlier, now languishes as a derelict on a Muscongus Bay beach—an eyesore to many, but an icon of the past to others. (LB2012.15.3323 from National Fisherman, August, 1984, page 1-C. Photo by Mike Crowley)

Another COLUMBIA. Built in the northeast (Rice Bros., East Boothbay, Maine) for service in the Pacific Northwest, this vessel had to steam many miles, before she could drop her anchor and take on duty at the mouth of the Columbia River. Built in 1950, and serving until replaced by a buoy in 1979, the vessel is now a National Landmark displayed at the Columbia River Maritime Museum. (LB2012.15.4779)

Pumping Menhaden. Also known as bunkers or pogies, these fish (most processed for bait and fertilizer) run in offshore schools so can be spotted from an airplane and encircled by a big purse seine, then compacted for pumping. The 163′ vessel, named W.J. BURTON, belongs to Omega Protein and is probably out of the company’s Reedville, VA, plant. She was built in 1966 by Burton Shipyard in Port Arthur, TX, near where the Gulf of Mexico’s menhaden school and near Omega’s headquarters. (LB2012.15.5567 from National Fisherman, August, 1986, page 16. Photo by Jim Thomas.)

Dredging Crabs. Looking toward the bow of the the 55-foot THOMAS W. as her pair of 7-foot-wide steel dredges scrape the bottom of Chesapeake Bay for crabs.(LB2012.15.3876 from the 1986 National Fisherman Yearbook, page 49)

Offshore Lobsterboat. Boats became ever larger as the supply of inshore lobsters diminished. They could get there faster and were better able to deal with bad weather. Lobstering was no longer a one-man operation, the boats now carrying one or more stern-men. The 49-foot SEA FEVER, designed by Aage Nielsen for his fisherman son-in-law, Bob Brown, was one of the early offshore boats, built in 1972 by Sonny Hodgdon of East Boothbay, Maine. She was followed a year later by the nearly identical FIONAVAR. (LB2012.15.5445 from National Fisherman, August, 1972, page 12-A. Photo by Boutilier)

When Traps Were Wood. So they’d sink to the bottom where the lobsters are, old-fashioned traps built of oak had to be ballasted with flat stones or concrete. The traps piled aboard SKIMMER in 1966 are headed for the lobstering grounds of mid-coast Maine’s Muscongus Bay, one of several such loads to be picked up and set from the boat’s home port of Round Pond.(LB2012.15.5151 from National Fisherman, January, 1972, page 10-C. Also in the 1990 Yearbook, page 67. Photo by Boutilier)

Setting Gear. Wooden lobster traps are built of laths nailed either to semi-circular bows or to straight-piece framework like these piled aboard for setting. Mornings, when the wind and sea are flat, is best for hauling as well as setting, especially when working out of small skiffs.(LB2012.15.4827 from National Fisherman, May, 1977, page 17-C. Also in 1981 Yearbook, page 58)

Hauling by Hand. Before engines, many lobstermen worked out of rowboats. Peapods were a favorite of near-shore lobstermen, being steady enough to row standing up, and sufficiently seaworthy to bring you back safely if the weather turned bad. Raised oarlocks and a big rail-mounted sheave were marks of a working peapod. Also, a tub for the bait and a box for the catch. This Merrill Young-built pod is now in the museum’s watercraft collection.(LB2012.15.5153)

Life Afloat. Spruce logs spiked together make for a low-cost raft, but a pretty flimsy one. Floating power is limited, so that after being weighed down by the shack, the freeboard is so scant it’s like walking on water. Great on a calm day like this, but there might be an “abandon ship” call when the wind stirs things up. (LB2012.15.5508. Photo by Myrick)

In 2012, Diversified Communications of Portland, ME, donated National Fisherman magazine’s entire pre-digital photographic archive to the Penobscot Marine Museum (PMM). Although the Museum has Fair Use rights to the images, responsibility for determining the nature of copyright and obtaining permissions to publish, transmit or reproduce these materials rests entirely with the researcher. You can view many more photos of this collection here.

Ben Fuller says:

The Matinicus double ender in .5153 is now in the PMM collection. Built by Merrill Young and fished by Oren Ames, up into the 80s working out of Matinicus. It’s hard to see in the photo but Ames didn’t bother to have a set of sockets to pull row his boat. We’ve two mismatched oars: one is ash and worn about half way through. The other is spruce with a piece of fire hose for chafing gear, probably replacing the mate to the ash oar.

Joe Morck says:

In the last photo I see a good luck horseshoe over the door with the open side up so all the luck doesn’t spill out. Just as I learned in the hills of Eastern Kentucky.

Judie Romeo says:

Hey Steve, Is that last photo the inspiration for your shack-float?!

Steve Stone says:

The schmee of it, yes. The floatation, well, it’d be nice to lounge on the deck without waders. And maybe if the roofline wasn’t held together with a 2 x 4?

Anne Bray says:

Terrific photos and captions.

David Tew says:

Great photos, memories stirred. I worked on a crew that built one of Aage Nielsen’s lobster boats like Sea Fever.