After time has erased coastal Maine’s old-time boats, wharves, and buildings, we turn to old photos for a glimpse of the coastal life that once was. A wonderful new source is the book Maine on Glass in which early 20th-century photos are beautifully printed and written about.

The book contains more than 200 glass-plate images, taken by the photographers of Belfast-based Eastern Illustrated & Publishing Co., of inland as well as coastal scenes. (The entire collection numbers more than 50,000 glass plate negatives.)

Co-authors Bill Bunting, Kevin Johnson and Earle Shettleworth, and co-publisher Penobscot Marine Museum, have made available here, for OffCenterHarbor members, all of the books’s maritime photos as well as the captions that go with them.

Maine on Glass is a first-rate production: co-publisher Tilbury House’s printing is fantastic. And it’s a real bargain, listed at only $29.95. For each photo, there’s an engaging caption written by Bill Bunting, king of the caption writers from whose work I’ve long been guided.

Be sure and zoom to fill your screen—and beyond. You’ll feel like you’ve stepped back about a century into a bustling world made mostly of wood.

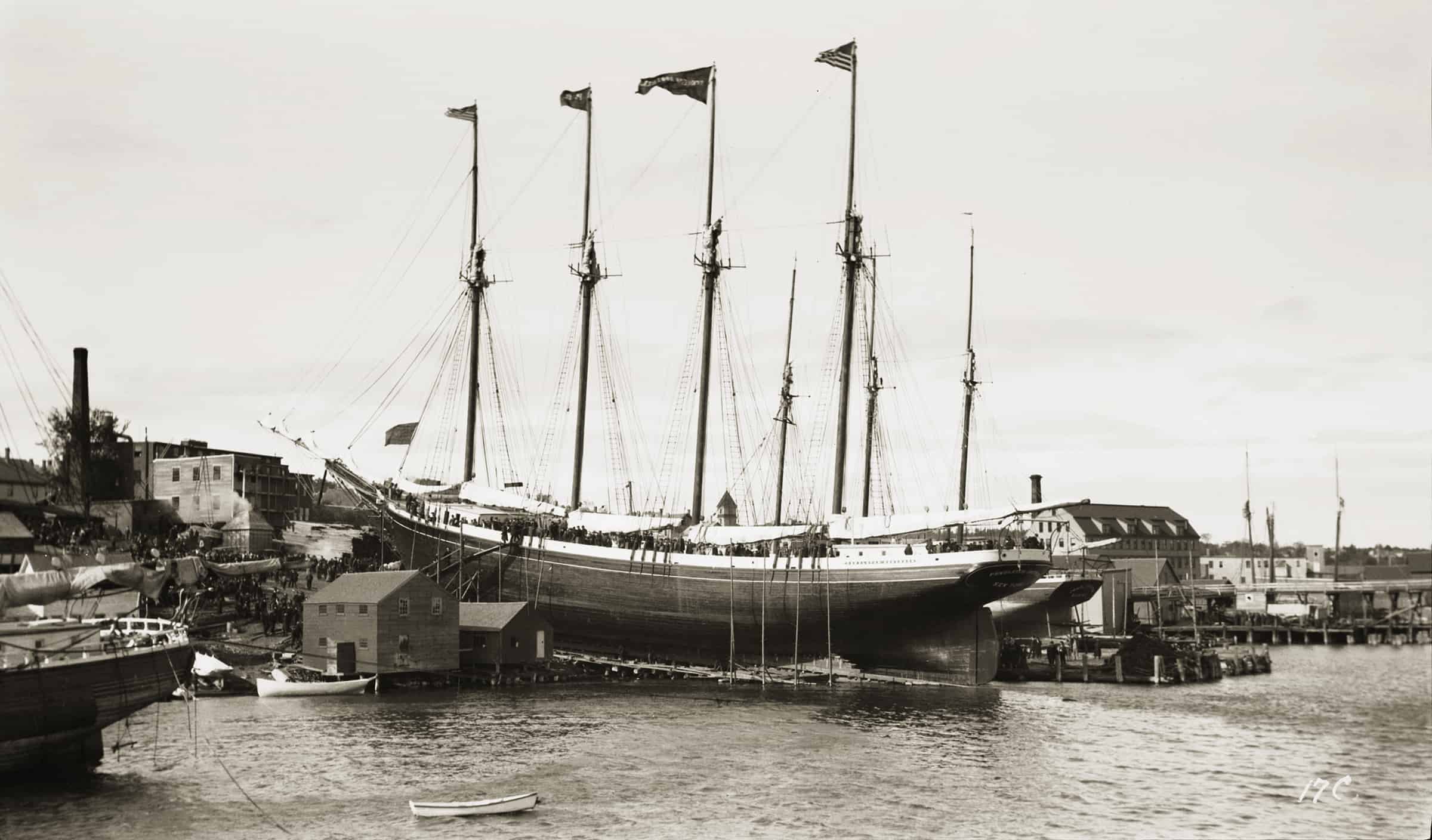

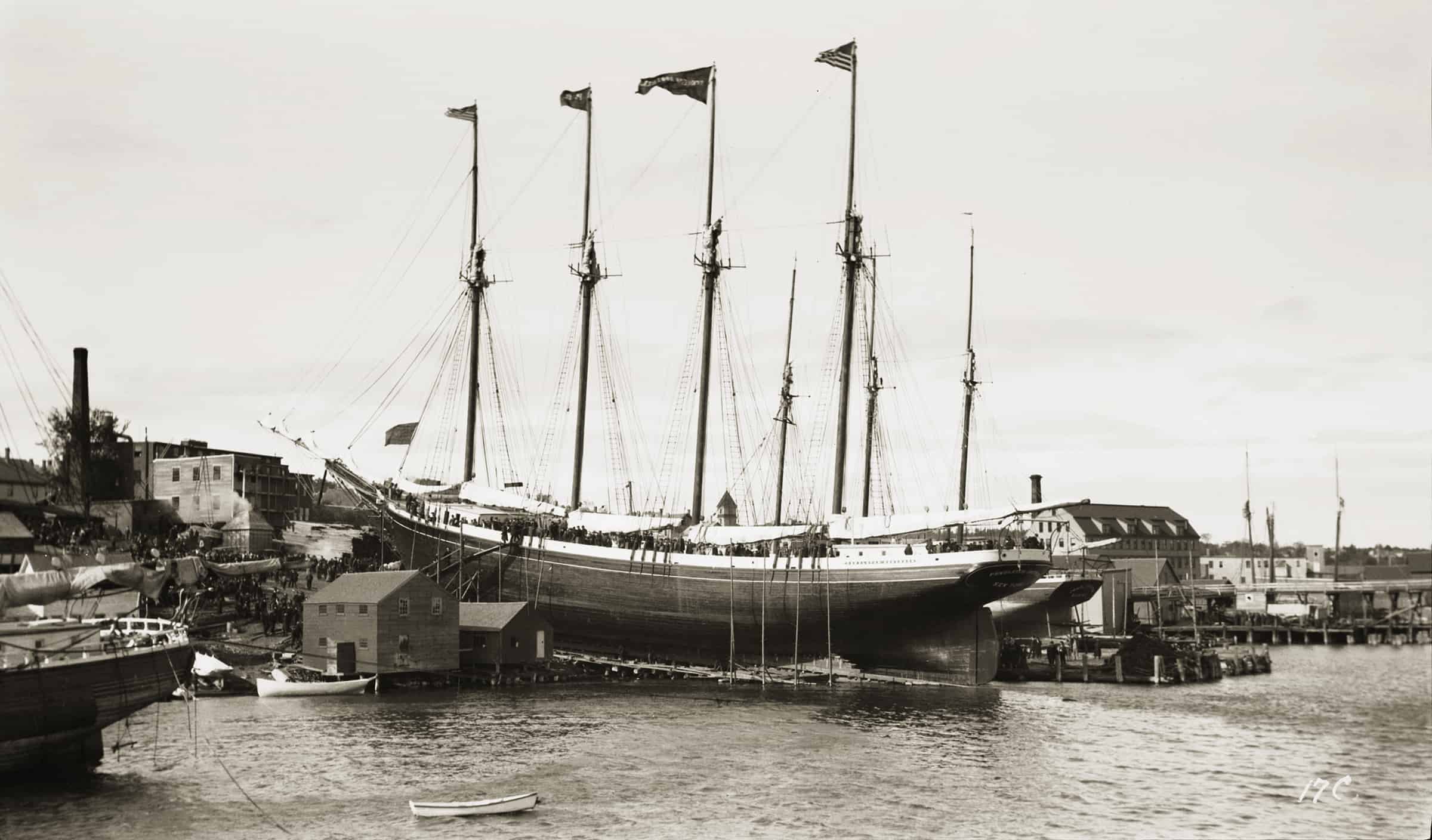

Schooner PENDLETON BROTHERS on the Ways: With guests packed on board and onlookers gathered ashore, the handsome four-masted schooner PENDLETON BROTHERS is launched from the Pendleton shipyard on October 22, 1903. Below her black waist she is painted a “bronze green” with a coppered bottom. The three-masted schooner beyond the PENDLETON BROTHERS is on the port’s 1,000-ton marine railway. Installed in 1885, it was horse-powered until converted to steam in 1900. In order to move the carriage 160 feet, the one or two horses on the sweep had to walk twenty-six miles. In the 1870s and ’80s, Belfast was home to a fleet of handsome, home-built centerboard three-masted schooners of shoal draft (to squeeze over the St. Johns River bar), carrying Waldo County ice and hay to Jacksonville. They returned with hard pine shipbuilding timber. Belfastians formed businesses, built a marine railway, and wintered in Jacksonville. An earlier PENDLETON BROTHERS built in 1899, also a four-master, foundered in 1902. The second PENDLETON BROTHERS went ashore in the Florida Straits in 1913. Her owners lost doubly, as she would have been worth a large fortune in the wartime boom a few years later. (MoG page 2)

Schooner PENDLETON BROTHERS on the Wavelets: “She floats!” A puff of white steam shows that the shrill whistle plumbed to the PENDLETON BROTHERS’ donkey boiler is adding to the excitement. The donkey engine hoisted the anchor and the sails, greatly reducing the size of the crew. Two wartime schooners aside, Belfast shipbuilding ended with the four-masted schooner PENDLETON SISTERS in 1906. Pendleton Brothers were New York shipbrokers, managing owners, chandlers, and insurance agents who hailed from (and summered on) Islesboro, and who owned outright, or shares in, about one hundred vessels. The PENDLETON BROTHERS was built and owned by Captain Fields C. Pendleton, the father of the brothers. Wooden ships were “modeled,” or designed, by carving a model. The PENDLETON BROTHERS, a thing of beauty, shares a strong resemblance with four Belfast-built four-masted, barkentine-rigged “coffee clippers” modeled by William Brown, who died in 1899. Conceivably the lines from one of Brown’s models could have been adjusted for the schooners. Stockton native John Wardwell, a former master builder in a Belfast yard and likely influenced by Brown, modeled vessels of similar grace. One of his finest creations, the four-master ROBERT H. McCURDY, was launched at Rockland this same day. (MoG page 3)

Steamer BELFAST at Belfast Wharf: Measuring 335 feet overall yet drawing only ten feet of water, the BELFAST and her sister CAMDEN must have been challenging to handle in confined harbors on windy days, even though the two outboard (of three) propellers could be backed independently. Discretion being the better part of valor, the departing sisters backed well down Belfast Harbor before turning to head up the bay. Steamboat pilots on this foggy coast had long relied upon the strong backing power of older side-wheelers to avert disaster. (MoG page 5)

Belfast Band Aboard Steamer BELFAST: The celebrated thirty-five-piece Belfast Band—along with the graduating class from Belfast High School and two hundred other special guests—boarded the new steamer for her first trip “up the river” from Belfast to Bangor. The band played for the welcoming crowds gathered at every landing. Town bands, heavy on brass and inspired by German immigrant “oompah” bands, flowered in the late 1800s. The Belfast Military Band was formed in 1889, and, “by indefatigable practice,” earned itself high demand for civic occasions, holidays, and excursions. The two drum majors were William H. Sanborn, who weighed 260 pounds, and Donald O. Roberts, who was, at 40 pounds, the smallest man in the State of Maine. Nationally, community bands went into a steep decline after the First World War. In need of new markets, instrument makers turned to promoting the teaching of music in schools. (MoG page 5)

Northern Maine Seaport: The Northern Maine Seaport, at Cape Jellison, an overly ambitious port facility, was built by the Bangor & Aroostook Railroad in 1905 as an ice-free outlet for potatoes, lumber, shook, pulp and paper, and for receiving fertilizer, coal, cement, paper-making supplies, and so on. A branch line connected with the main line at Lagrange. The white potato house measured 600 by 125 feet and could hold 240,000 barrels. Electricity from an on-site powerhouse moved the potatoes about and bagged them for shipment. Italian laborers built it all. A great future for the new port was predicted, but after several busy years, shipments declined as timberlands were depleted, the potato boom slumped, fertilizer plants were built elsewhere, and freight transport by rail increased. In 1924 it all went up in smoke. At nearby Mack Point, in Searsport, where a coal pocket was built, shipping continues to this day. The four-masters D. H. RIVERS, at center, and the L. HERBERT TAFT, whose stern is seen at left, both hailed from Thomaston and were owned by the firm of Dunn & Elliot. Possibly they arrived with phosphate from Tampa. The square-rigger—she is a bark—may be Italian and loading hardwood fruit-box shook for Sicily. (MoG page 8)

Steamer CASTINE: The smart little steamer CASTINE lands passengers at Smith Wharf, Islesboro, from which she ran to and from Belfast in one phase of her forty-one years of service. A crisp and brisk northwest wind furrows the bay with whitecaps and threatens to blow the ladies’ hats off. Only the weary carriage horses appear unmoved by the stimulating scene. CASTINE, and the smaller GOLDEN ROD, were owned and operated by the colorful Coombs brothers, Leighton, Perry, and Fred. Leighton and Perry were captains, Fred was an engineer (as was Leighton also). The boats were among two dozen or so small steamers that ferried people about Penobscot Bay. None were better maintained. Nor was any captain more agile than Leighton, who could jump from one barrel into another, nor more saving of coal than Perry, who banked the fire as soon as the boat was alongside a wharf. And no boat had a longer career than did CASTINE, nor met such a tragic end as she did on a Vinalhaven ledge in fog in 1935, with the loss of four lives. Islesboro had four steamer landings, reflecting both its long, skinny shape and the long-lived prohibition against automobiles, kept in force by the summer colony’s threat to decamp and take their money with them if it was rescinded. Livery stable owners had difficulty recruiting enough horses and workers to meet the high demand for transportation in the short summer season. (MoG page 12)

Schooner ALICE E. CLARK: The four-masted schooner ALICE E. CLARK lies hard aground on Coombs Ledge in West Penobscot Bay, off Islesboro. Built at Bath in 1897, the CLARK had enjoyed a career that, by the standards of her kind, was nearly unblemished. On July 1, 1909, however, she was headed up the bay for Bangor with 2,717 tons of coal when she went to the wrong side of the buoy marking the ledge—Captain McDonald blamed a low-lying haze. Although sailing slowly, she impaled herself, thwarting extensive and expensive efforts at salvage. Presumably these boatmen have legitimate reasons for boarding the CLARK, and are not among those generally law-abiding coastal residents who were transformed into members of the genus piraticus upon the occasion of a bountiful shipwreck. One might expect the coast of Maine to be littered with wrecks, but such was not the case. For example, of about 520 four-masted schooners built on the East Coast—over 320 of them Maine-built—only three were wrecked in Maine waters, all in Penobscot Bay. Explanations include the fact that big schooners spent most of their careers elsewhere; shipping along the Maine coast was much reduced in winter; unlike Cape Hatteras or Cape Cod, most of the Maine coast offered harbors of refuge in an easterly gale; and the Maine coast was well supplied with lighthouses. Many of the schooners wrecked on Hatteras were southbounders caught trying to slip by between the Outer Bank beaches and the north-flowing Gulf Stream. (MOG page 13)

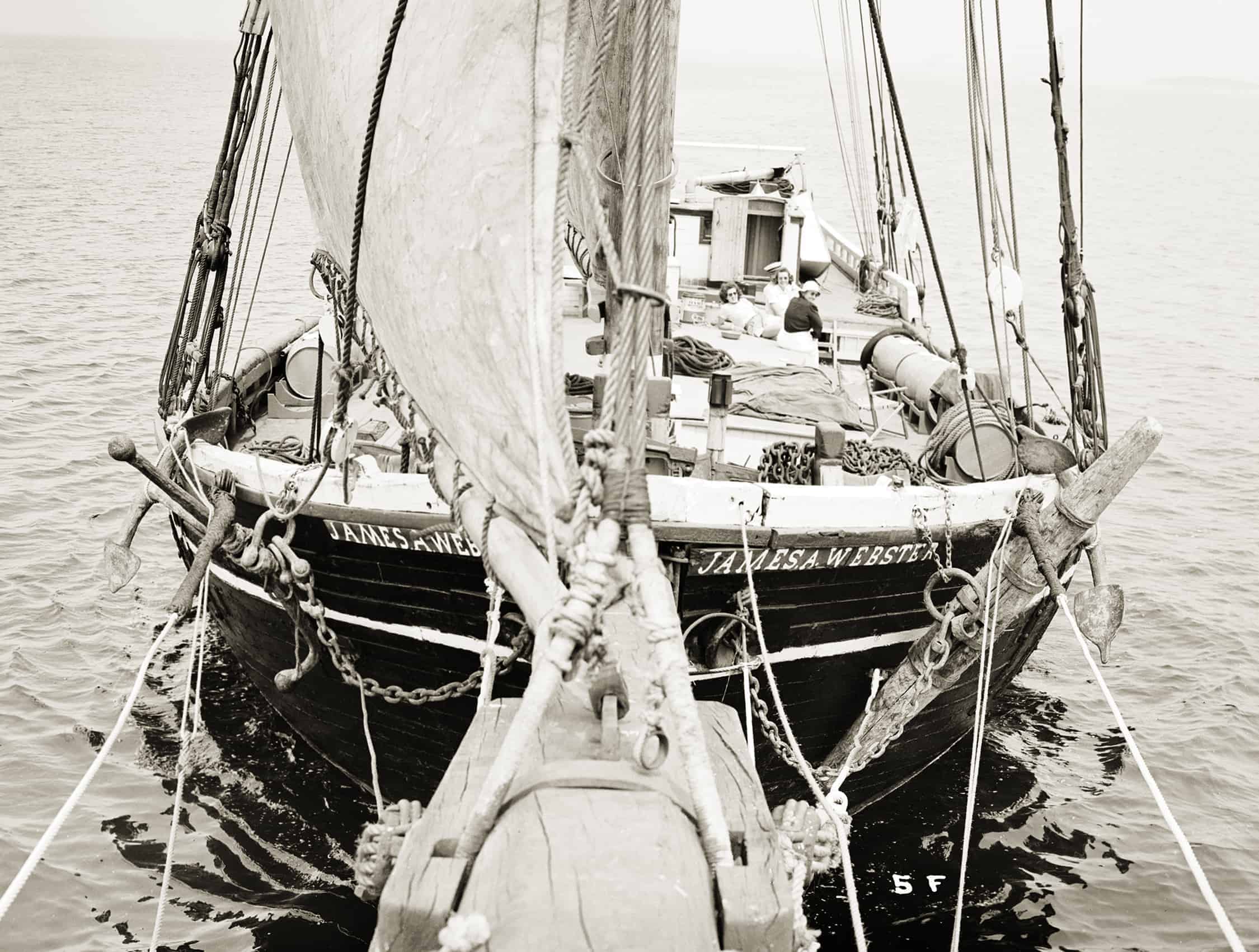

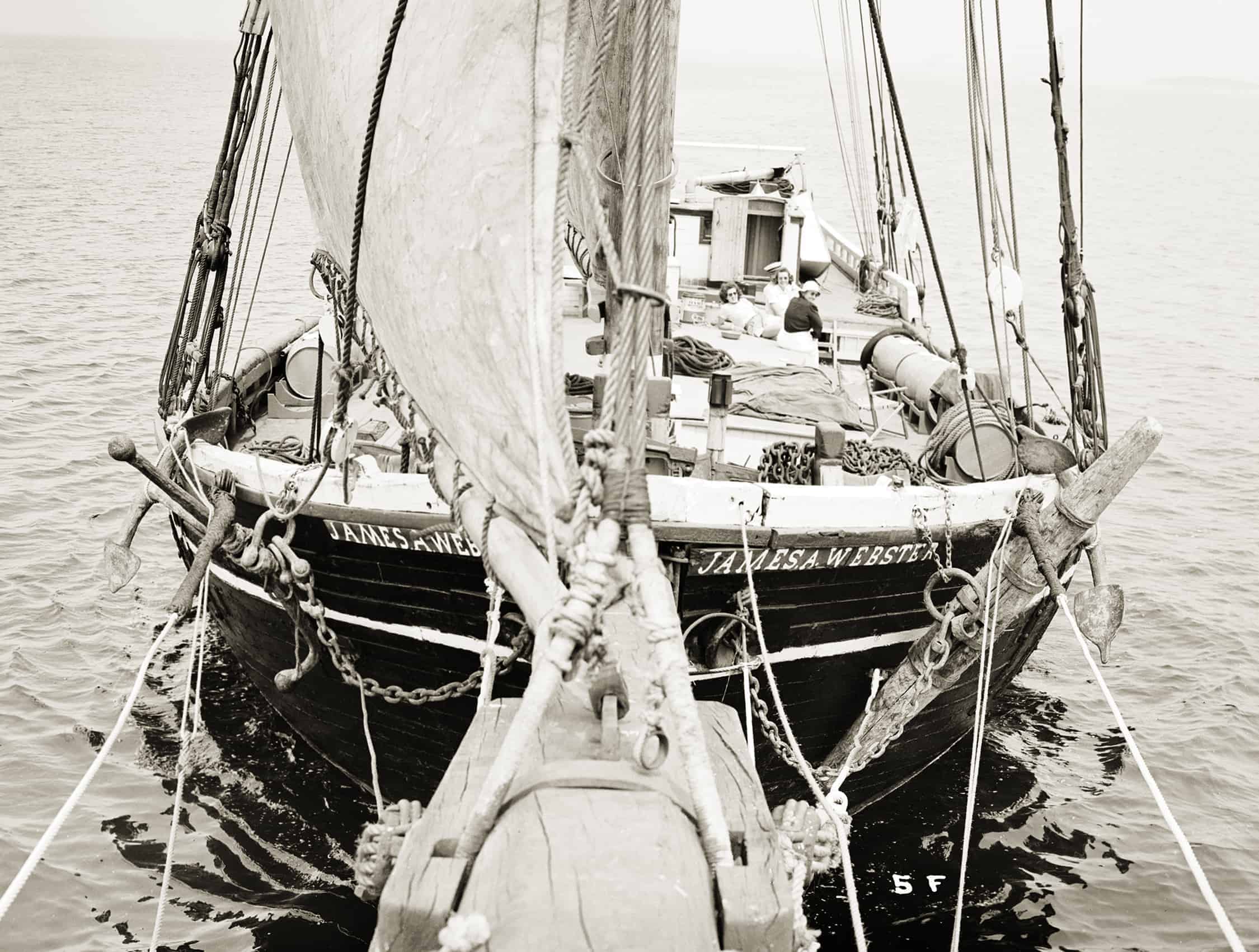

Schooner JAMES A. WEBSTER Under Sail: The “dude schooner” JAMES A. WEBSTER, of Rockland, lazes along circa 1945. Built at South Brooksville in 1890 to carry general cargoes, the old schooner looks remarkably good for her advanced age. She is still carrying topmasts and setting a main topsail and a jib topsail. In a final bid for survival, the WEBSTER’s owner is following the example set by Captain Frank Swift of Camden. In 1936 Swift began buying up old “bay coasters,” throwing up partitioned cabins in the cargo hold and hiring old captains out of retirement to sail them on protected Penobscot Bay with passengers. (MoG page 20)

Schooner JAMES A. WEBSTER Deck View: Passengers relax on deck. Living conditions aboard the old schooners were basic—fresh water was carried in casks on deck—but that was all part of the charm. For young single women, in particular, dude cruising offered an economical taste of seagoing adventure without danger of seasickness or having to fend off the obnoxious mashers infesting conventional resorts. The business extended the active lives of a number of vessels, but as it was cheaper to buy another schooner than to pay for major repairs, for most it was but a brief reprieve from the final mudbank. The WEBSTER was soon shifted to Long Island Sound, perhaps to be nearer to the source of single secretaries and school teachers, but lasted in business there only a season or two. The “windjammer” fleet on Penobscot Bay, however—the term “dude schooner” is passé—not only survived but eventually thrived, both with rebuilt relics and, beginning in the 1960s, the addition of several fine new vessels. The WEBSTER’s raised poop and stanchioned fly rail, a common feature of larger schooners, was unusual for a two-master. (MoG page 21)

Carvers Harbor, Vinalhaven: This island town was a busy place in the early 1900s, cutting granite, catching and curing fish, coopering, making glue, and knitting fly netting for horses. Across the harbor we are looking at the buildings of the Lane–Libby Fisheries Company, which annually cured six to eight million pounds of groundfish obtained from local boats and smaller dealers along the coast. Most was sold in the northeast states as boxed boneless fish, while large quantities of hard dried fish were shipped to South America and the West Indies. Fertilizer, glue, oil, and dried sounds (swim bladders, used to settle beer and make isinglass) were byproducts. Had the photographer arrived on another day, an Italian salt bark might have provided a picturesque centerpiece. We do see Friendship sloops, likely most now with motors. The floating machine shop and the gasoline barge are manifestations of the internal combustion revolution. The small, lofty schooner is a puzzler—she looks like a yacht-like pre-engine-revolution lobster smack. The three-masted schooner has likely come to load paving or salt fish. Dories ride on moorings, while two high-sided peapods and a skiff are tied to a lobster-storing “car” in the foreground. (MoG page 22)

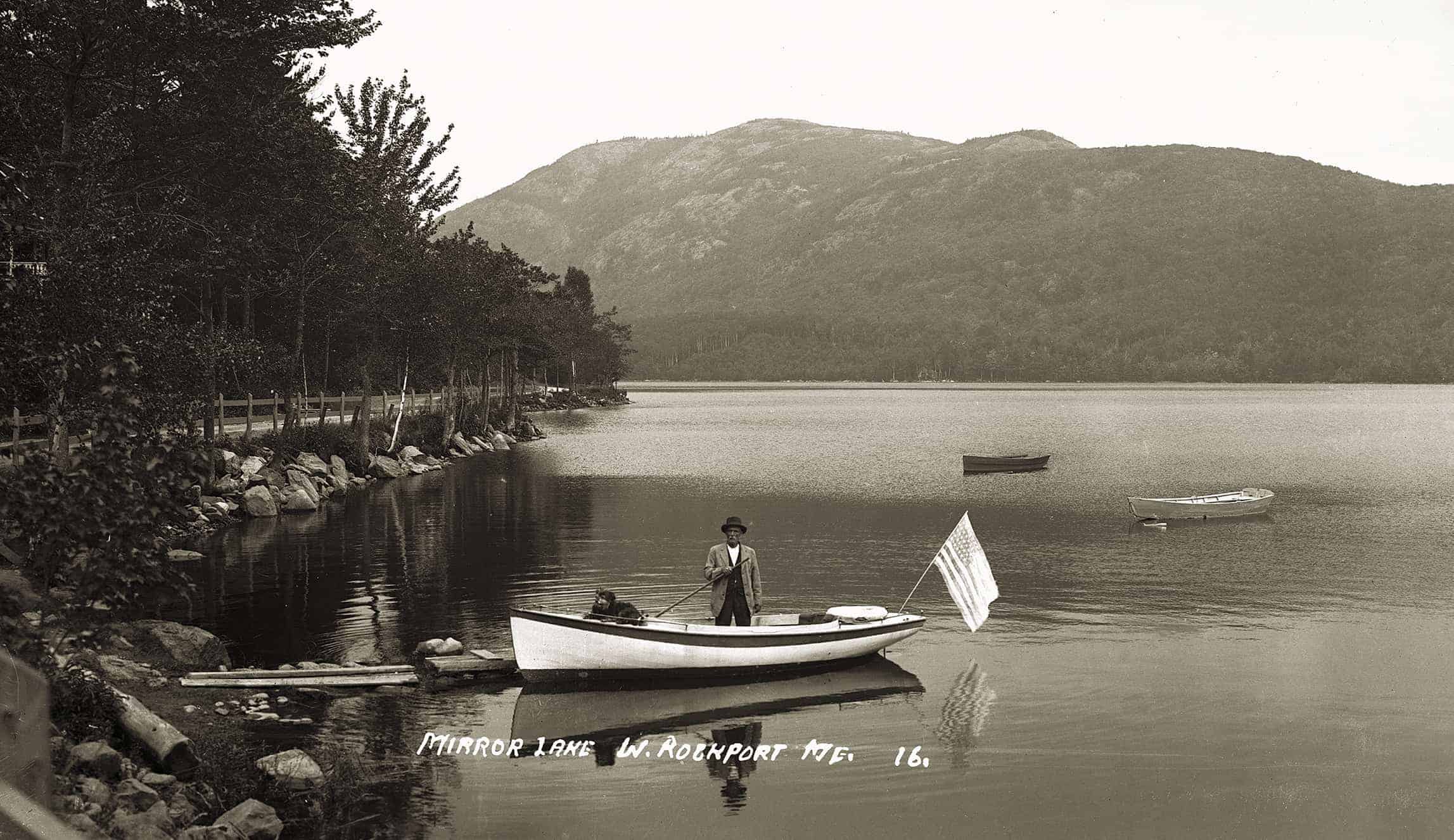

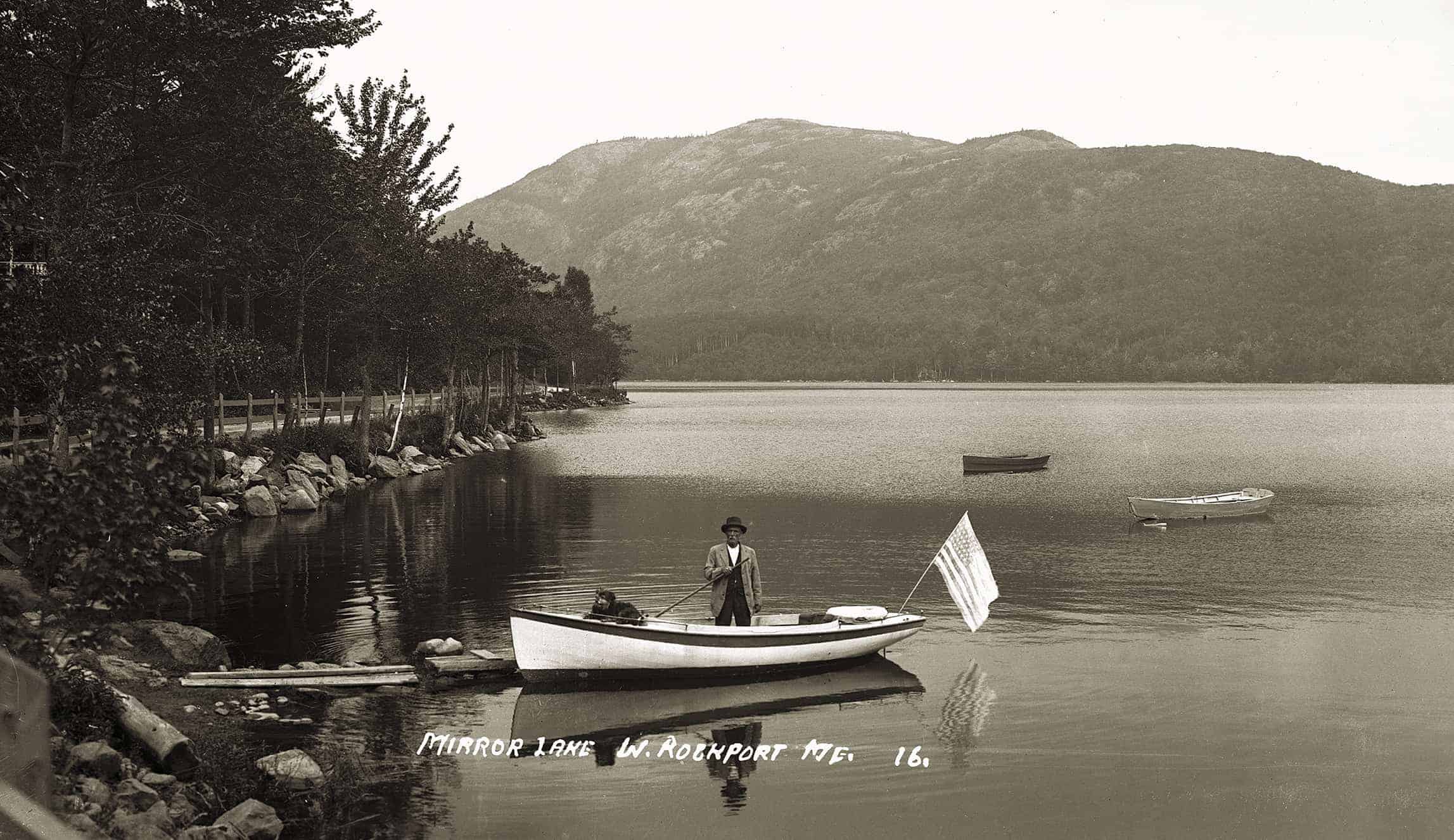

Mirror Lake, West Rockport: Mirror Lake looks as inviting here as it sounds in a July 1898 description in the Maine Central, a Maine Central Railroad publication promoting tourism: Camden offers more varied attractions than any other resort on the entire coast. When one tires of the smiling, surging, shifting sea, he has but to turn for diversion to the mountains and the scores of charming lakes with which the place is surrounded. Within a distance of ten miles there are equally as many charming ponds where a summer day may be spent fishing, picnicking, or viewing the sylvan beauties of nature here so lavishly displayed. Mirror Lake is located high up among the mountains, at an elevation of three hundred and fifty feet above the sea. It is but six miles away, and its crystal water supplies the town. Today’s view of Mirror Lake mirrors that of one hundred years ago aside from the fact that the sylvan lakeside lane has become roaring Route 17; a communications tower surmounts nearby Ragged Mountain; and no boats, persons, or dogs are allowed on or near the water. On the other hand, there are fewer telephone wires (upper left). With backup from Grassy Pond and a brook, Mirror Lake remains the water supply for several towns. (MoG page 25)

Barkentine REINE MARIE STEWART: The barkentine REINE MARIE STEWART is berthed in Thomaston Harbor in this view across the Georges River from the Brooklyn Heights neighborhood, likely so-called because prominent Thomaston shipowners had moved to Brooklyn Heights, New York, by the East River, the better to oversee their ships and businesses. Stratospheric shipping rates brought on by World War I attracted both speculative plungers and the staid Thomaston firm of Dunn & Elliot, longtime sailmakers, shipbuilders, and shipowners. Not having built a vessel since 1904, their once-large fleet of schooners had dwindled to four, and so, in 1917, they went back to work. By 1920 they had built a four-masted schooner, twin four-masted barkentines, and a five-masted schooner. The five-master, the EDNA HOYT, built in 1920 for $200,000, sold four years later for $25,000 as the bottom fell out of the shipping business. The twin 1919 barkentines, the CECIL P. STEWART and the REINE MARIE STEWART, found cargoes as best they could, mostly in coastwise trades, although the REINE MARIE made a voyage to Greece. In 1927 the CECIL P was lost on the New Jersey shore, and in 1928 the REINE MARIE was laid up at Thomaston, awaiting better times that never came, becoming a mouldering photographic icon. In 1937 she was sold to Nova Scotian owners and re-rigged as a four-masted schooner. In 1942, with tonnage again in demand due to war, she was purchased by Boston owners and sailed for West Africa. Off Sierra Leone she was sunk by an Italian submarine. (MoG page 28)

Schooner ABBIE BOWKER: The three-masted schooner ABBIE BOWKER, of Thomaston, is loaded by the “Black Maria,” which operated at the Booth Brothers quarry from the 1870s until Booth Brothers was one of several large quarries in St. George, in addition to numerous small, one-man “motions.” Maine’s extensive granite industry after the Civil War was the result of many factors, including architectural styles, construction technology, stone qualities, the availability of water transport, the budgetary surplus of the federal government, and politics, crooked and otherwise. Granite’s grains, which permitted it to fracture along fault lines into sheets, made it both feasible to quarry and a valuable construction material. Long Cove produced “dark granite,” a very closely grained stone which “hammered very light” but took a dark, high polish and fractured in thin sheets. The BOWKER was built at Phippsburg in 1890. A small three-master, in 1914 she loaded a cargo of 32,300 blocks at a Vinalhaven quarry, whereas the three-master JAMES ROTHWELL, which preceded her there, loaded 77,000. In 1918 the BOWKER stranded and was lost in the Bahamas. (MoG page 31)

Dresden Ferry: This image of the Dresden-Richmond ferry across the Kennebec River was presumably taken before circa 1916 when two new ferry scows were built. Although now powered by a motorboat, this scow still has a pulley fitted for the cable laid across the river bottom along which the scows previously ran, as well as the mast for the sail formerly carried. Originally separate ferries ran from Richmond and Dresden, and from Dresden to Swan Island; later they came under one charter. Interviewed in 1904, retired ferryman Joseph G. Densmore, who had served from 1859 until 1897, calculated that he had voyaged 237,500 miles all while crossing the Kennebec—the equivalent of ten times around the world. The ferry season usually ran from early April, when the river opened, to December 1. The ferryman was obligated to transport passengers at any hour, although after 9 p.m. he could double his rates. Mr. Densmore commonly made twenty-five trips a day. On one day he and his son ferried across the thirty-five teams of a traveling circus. After one horse panicked and took its rider and wagon overboard, the two Densmores were able to free it from its harness so that it could swim ashore. The wagon was salvaged later. (MoG page 51)

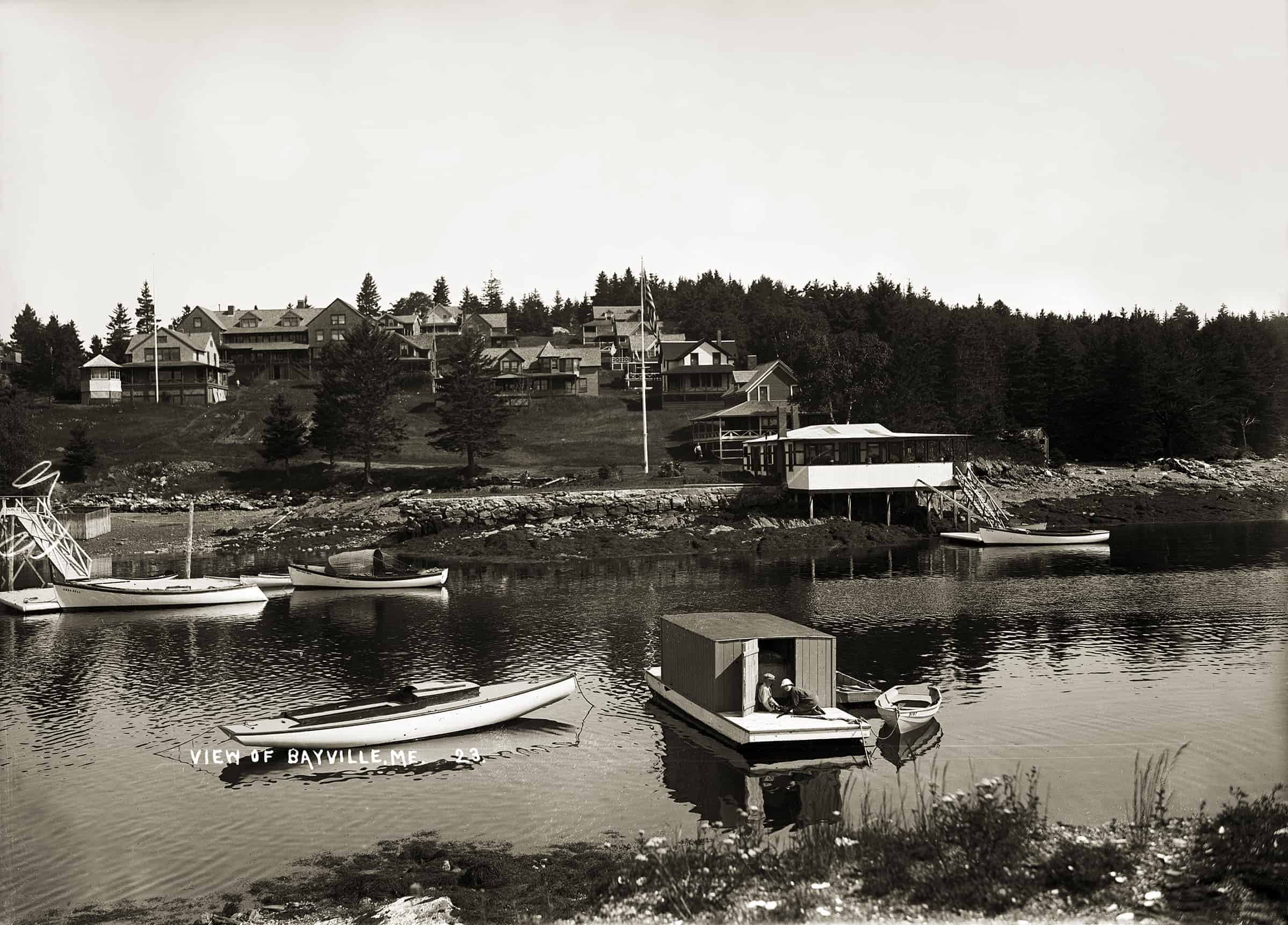

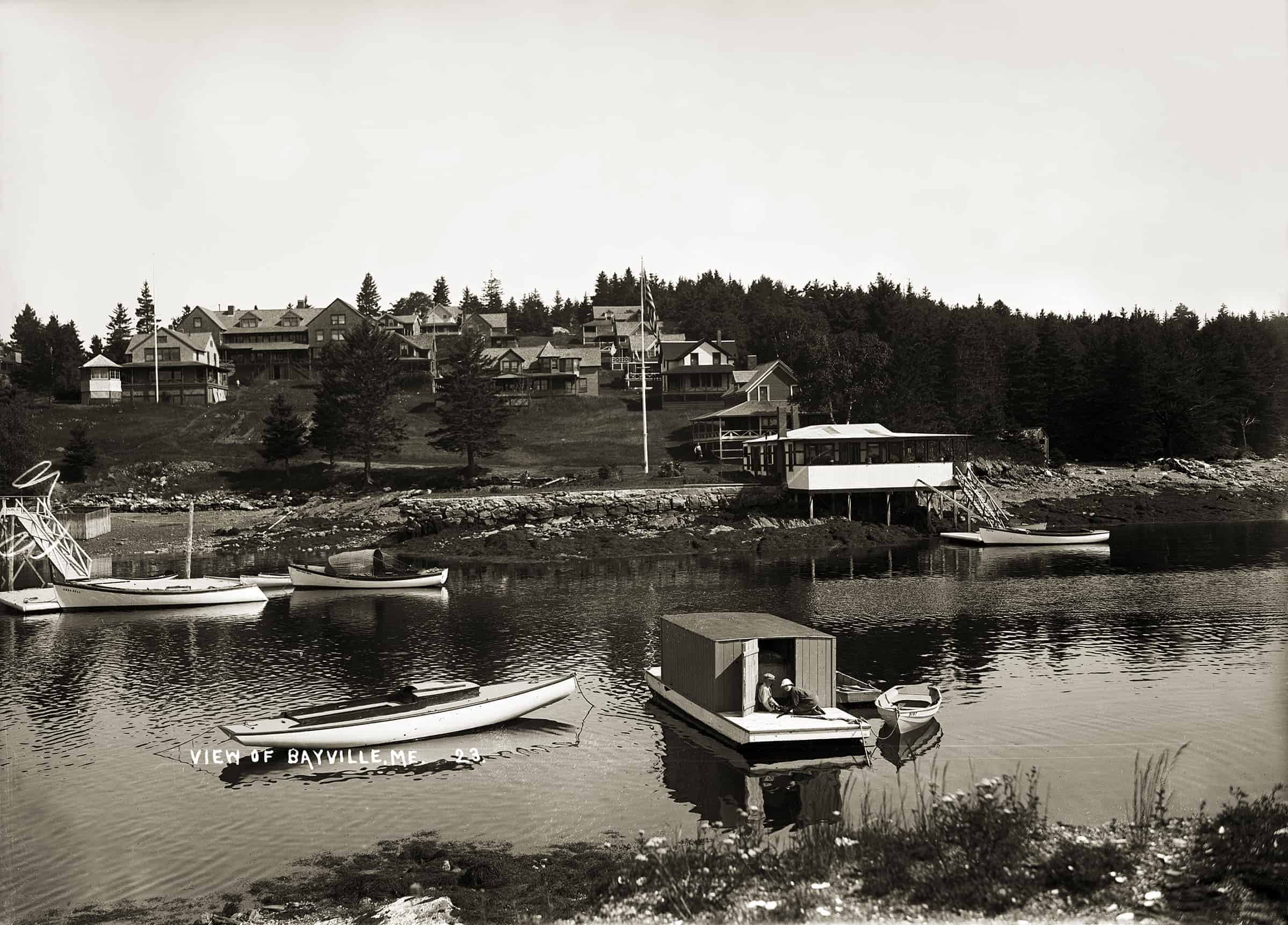

Bayville: Bayville in East Boothbay was one of many post-Civil War summer colonies in the region, including Ocean Point, Murray Hill, Paradise Point, Christmas Cove, Squirrel Island, Mouse Island, Isle of Springs, and Capitol Island. Some were developed by—and for—inland Mainers, while Bayville’s cottagers came in large part from the Boston area. Colonies typically sprouted on thin-soiled shore land or islands formerly considered of small value; indeed, Bayville’s site was called Hardscrabble. A local, Thomas Boyd, first attempted the alchemy of turning its ledge-rent lots into gold coin in the 1860s, but real development began in the 1880s. By 1904, a hotel was followed by about thirty-five cottages with seasonal piped water and electricity. In 1905 there were 574 non-resident taxpayers in the towns of Southport, Boothbay Harbor, and Boothbay, leading to agitation by the “summer complaints” regarding their taxation without representation. In 1911, following Squirrel Island’s lead, Bayville became an incorporated village within the town of Boothbay. The large edifice left of center was the hotel. At far left is a glimpse of the seal pen belonging to Captain Angus and Janet McDonald, who for years netted seals and sold them as public attractions all over the East, including Coney Island. In the forewater, a sloop awaits its mast. (MoG page 52 & 53)

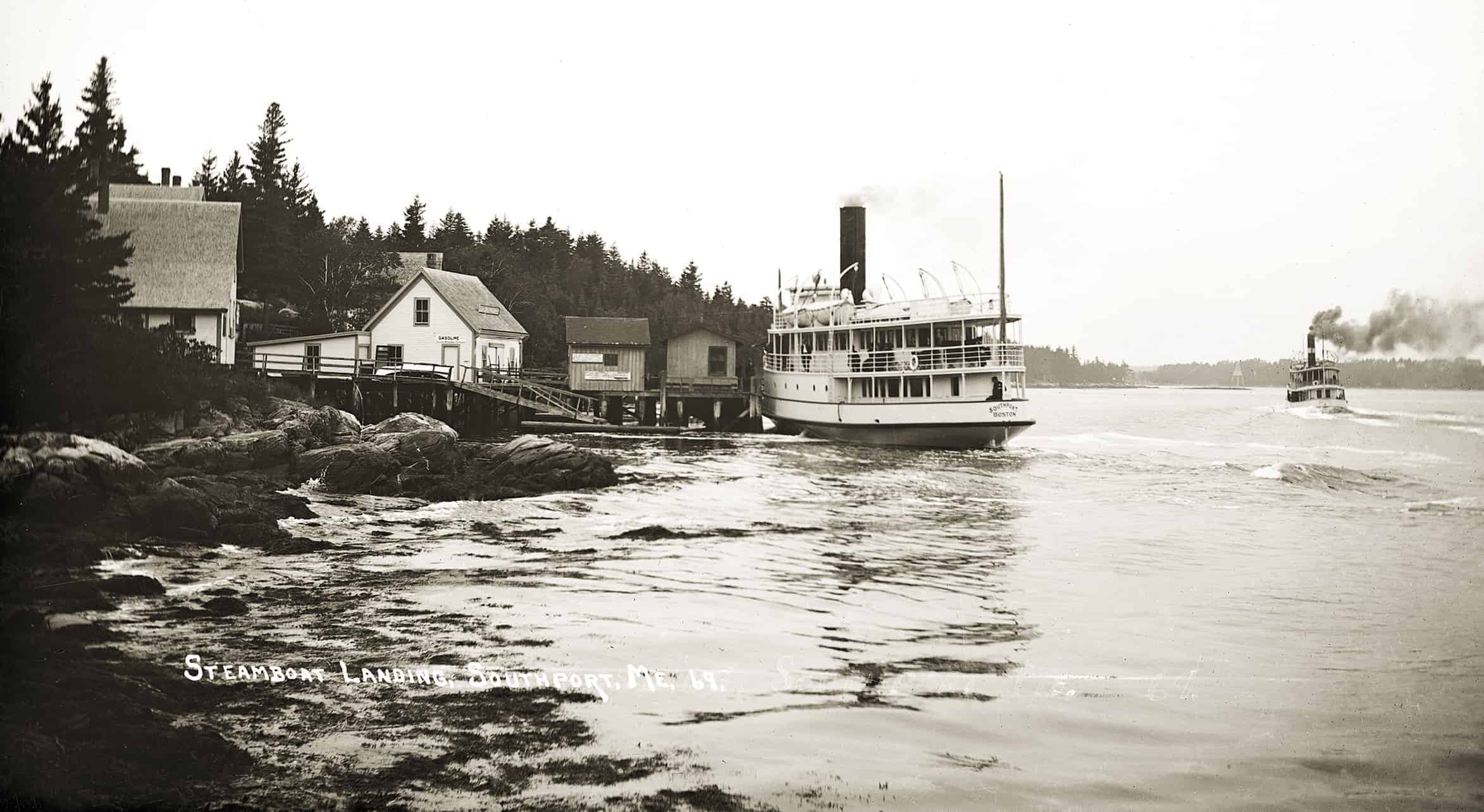

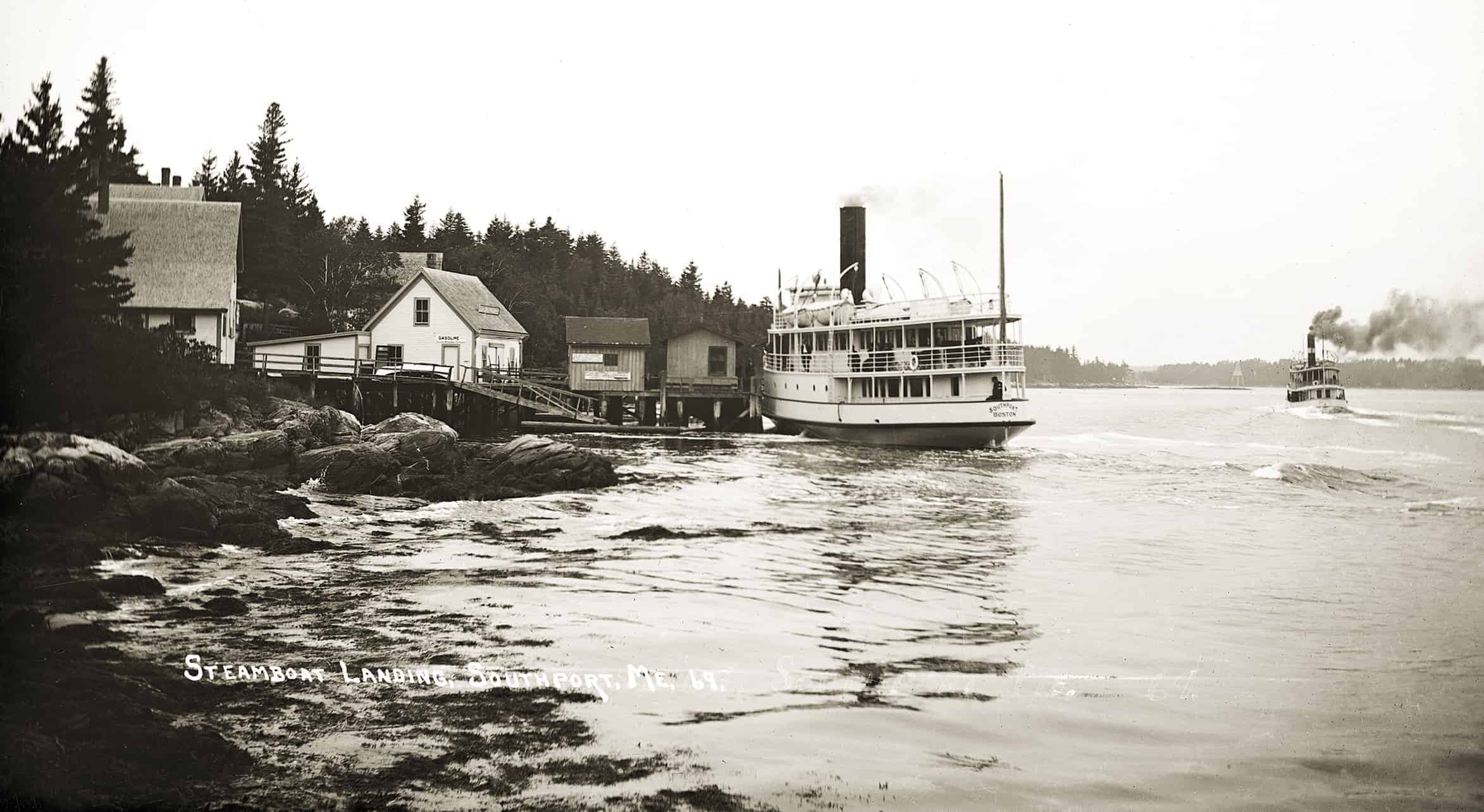

Southport Steamers: The Eastern Steamship Company’s SOUTHPORT calls at a landing in her namesake town while the smaller ISLANDER (the second of this name on the route) steams west through Townsend Gut headed for the Sheepscot River, Goose Rock Passage, Knubble Bay, and the narrow Sasanoa River (where, at Lower Hell Gate, the tide pulls the spar buoys under) on the inside passage from Boothbay Harbor to the Kennebec River. SOUTHPORT will follow ISLANDER to Bath, from whence Islander will continue up the Kennebec to Gardiner. SOUTHPORT and her sister WESTPORT, although built for this service in 1911, proved too big, and by 1920 both had shifted to the Rockland–Blue Hill line. The last of many steamers on the route was the VIRGINIA, in 1941. Small steamers serving islands and peninsulas long constituted a valued social and economic institution. They operated in watery realms unknown to rail or auto travelers, and the skill and nerve required to safely pilot them in fog and darkness were surely never fully appreciated by freight shippers or passengers. Unlike barking locomotives or puffing harbor tugs, the little steamers, fitted with condensing engines, glided along with just enough noise and vibration to reassure the timid. Memories of the sound of their whistles and the sweet smell of soft coal smoke—if not the accompanying soot—were long cherished after motor vehicles and highways did the little steamers in. (MoG page 56 & 57)

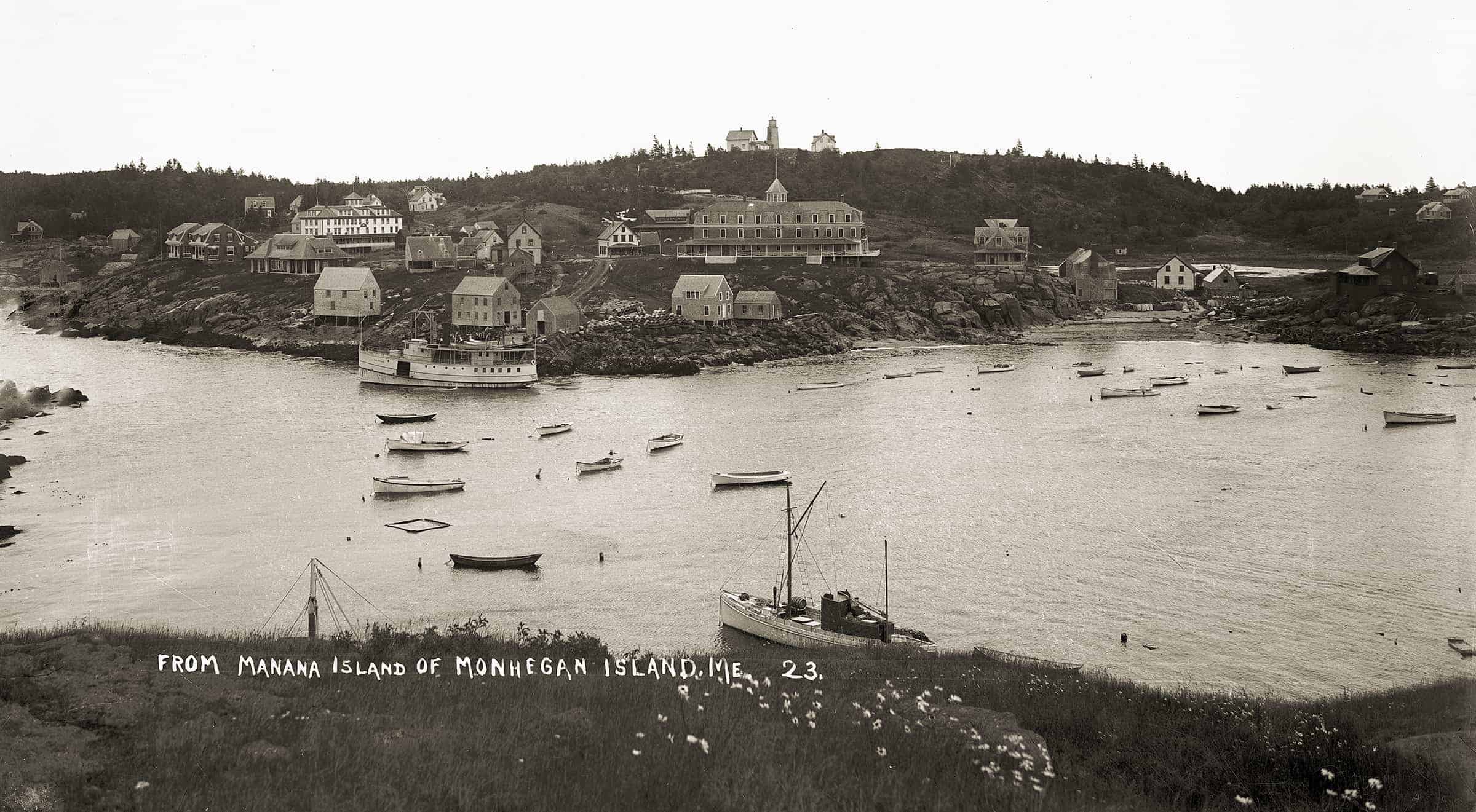

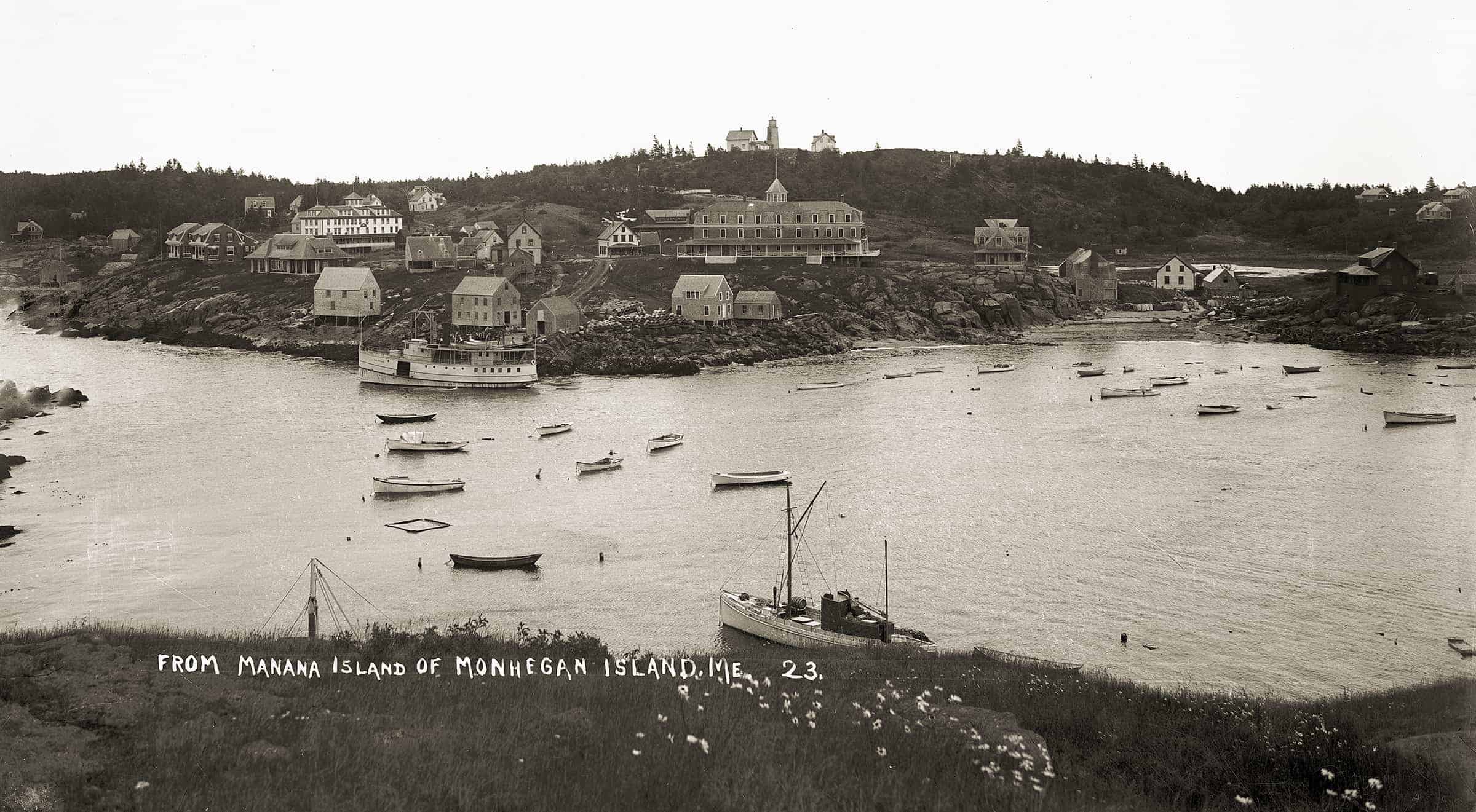

Monhegan Harbor: The steamer MAY ARCHER in Monhegan’s harbor, such as it is, circa 1910. The MAY ARCHER was built at Rockland in 1906 for Captain I. E. Archibald. In 1907 she delivered building materials for the new Island Inn, the large hotel at center. In 1908 Captain Archibald instituted a summer service from Thomaston to Port Clyde to Monhegan to Boothbay Harbor, and return to Thomaston. The island became a great draw for visitors, with alarming sea conditions in the harbor often adding to the adventure, a case in point being this report from the Brunswick Record, reprinted in the Belfast Republican Journal, September 3, 1908: They had the first big blow of the summer out at Monhegan last Saturday as it was so rough that the steamer MAY ARCHER could not make its landing at the wharf. There were half a hundred summer people anxious to get to the mainland, but they had to remain where they were, except six more venturesome persons who were taken out to the steamer in dories and pulled aboard at the end of ropes. Long before Boothbay Harbor was reached these six wished they had remained with the others, for the big waves had no end of sport with the steamer. However, she kept afloat and they suffered no worse fate than seasickness. Monhegan has hundreds of visitors this summer and the three hotels are all filled. From January 15 to May 28, 1910, island fishermen landed 58,500 lobsters, averaging $460 per man. Most of their boats were powered. The large vessel moored at right foreground has a seine dory astern and what appears to be a seine net flaked down aft; she is likely a herring seiner. (MoG page 59)

Woolwich-Bath Ferry: The ferry HOCKOMOCK, poised to cross the Kennebec River from Woolwich to Bath. She carries a mixed cargo of horse-drawn and motorized vehicles, and passengers. Pearline (see posters) was a laundry soap. The history of ferry service between Bath and Woolwich is a tortuous saga of rowboats, scows (with swimming oxen tied astern), a horse-powered boat, and many years of frustration. The first steam-powered ferry was the 1837 side-wheeler SAGADAHOCK, which ran on no fixed schedule. Other boats followed, but after the Knox & Lincoln Railroad began its own ferry in 1871—a colorful saga in itself—there were years when steam service ceased on the old line. From 1876 until its end in 1927, the “ People’s Ferry” became a municipal (later, a state) burden. The HOCKOMOCK—or “HUNKY-DINK”—a double-ended propeller boat, was launched in 1901, joining the old UNION, or “ONION.” In 1910 they carried 1,961 automobiles, rising to 15,000 in 1916. In 1920 the HOCKOMOCK and the GOVERNOR KING, a secondhand New York Harbor ferry, carried 31,7347 passengers, 51,200 autos, and 10,021 horse-drawn vehicles, while the UNION carried 54,000 passengers and 7,700 vehicles. Summer traffic delays of several hours were not uncommon, and in 1927, mercifully, the Carlton Bridge, which carried rail, vehicular, and pedestrian traffic, opened. (MoG page 62&63)

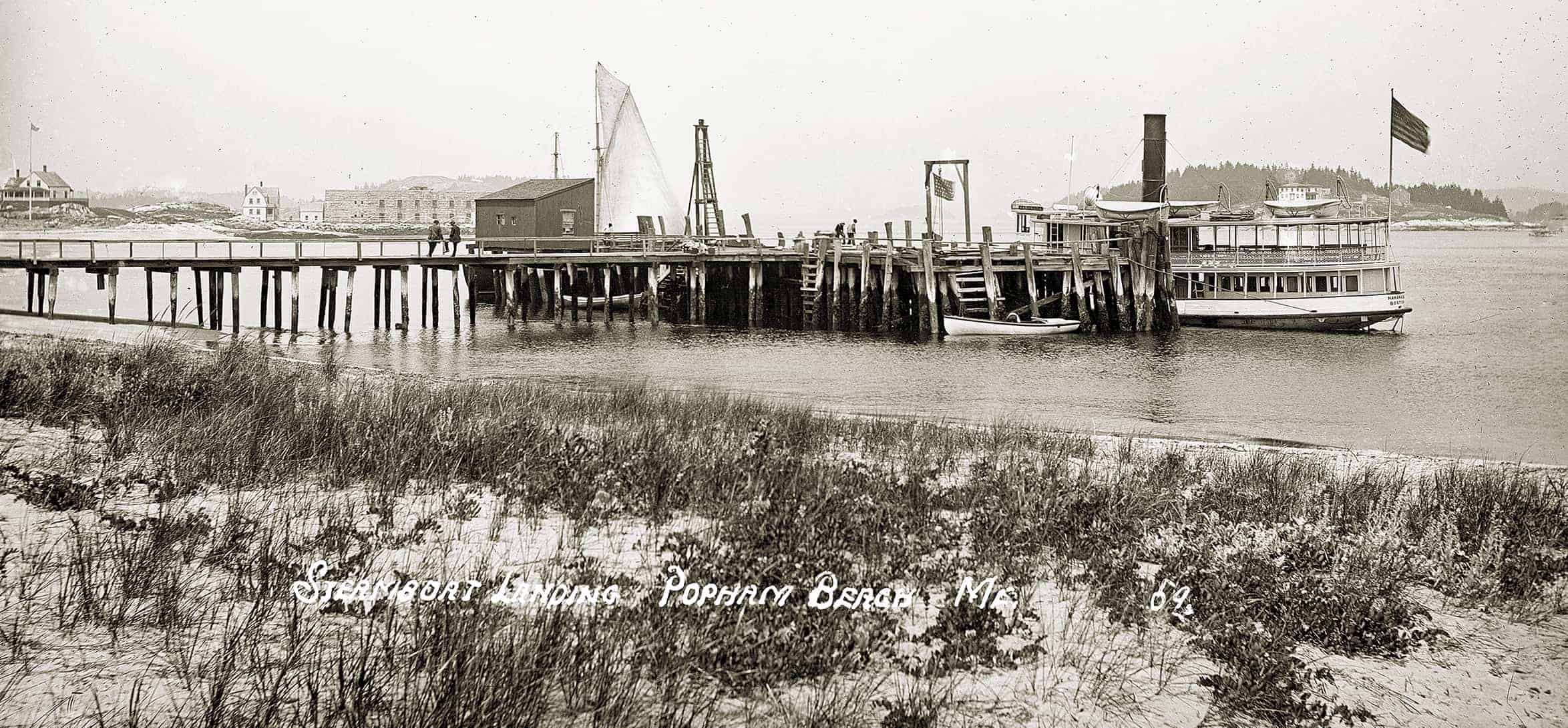

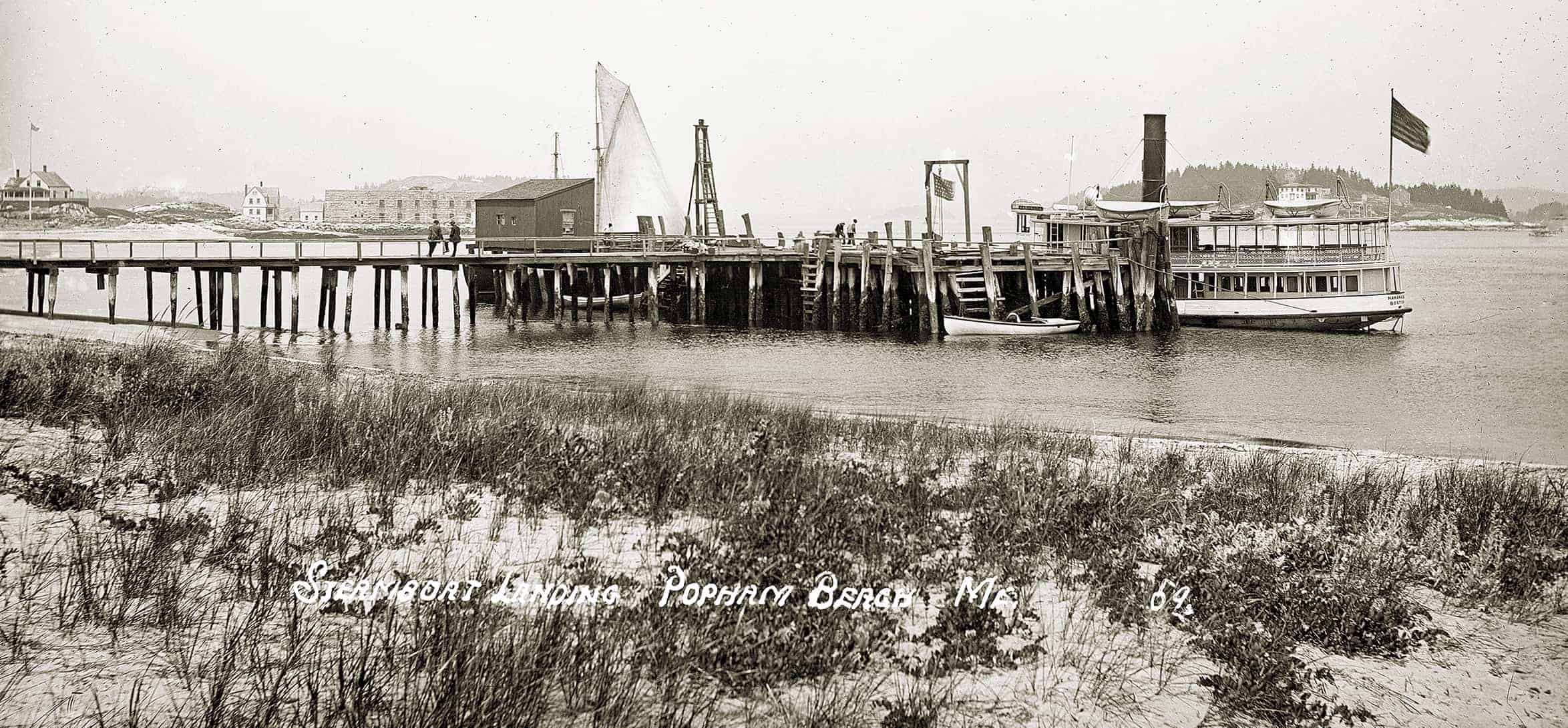

Popham: Popham Beach, at the mouth of the Kennebec River, beckons on a hazy day. Few locations in Maine had (or have) a stronger sense of place than Popham. In the early 1900s one could still get a sense of what the river was like in the late 1800s, when it was deemed the busiest in the nation, thanks to the booming summer ice-shipping business. With a southwest breeze blowing away the mosquitoes, one could watch the Boston steamer, paddles thrashing, depart for the westward, while inbound ice schooners, gray sails filled and taut, headed in for the river and the anchorage at Parker’s Flats. At twilight, the brilliant beacon atop the outlying sentinel of Seguin Island faithfully made its appointed revolutions. Very few resorts east of Scarborough could boast of a beach such as Popham’s. The little steamer lying at the Eastern Steamship wharf is the NAHANADA. Built in 1888 for the Bath–Boothbay Harbor run, she remained in service in those waters until 1925. Here, she is likely awaiting the return of her excursion party. The rig of the schooner obscured by the wharf suggests that she is a small shore fisherman. Beyond, at left, are the granite walls of Fort Popham. (MoG page 67)

The Basin: Whether through artistry, serendipity, or both, this is a masterful image of fishermen’s dories moored at The Basin. The brooding mass of the ledges contrasts with the fragility of the saucy floating dories, rugged craft though they may be. The permanence of the rock contrasts as well with the flaking emulsion from the bottom of the plate. If the author may be forgiven for quoting himself from another book, “Old glass plate negatives are but a thin emulsion over the dark void of eternity.” So there.

Camp Wyonegonic: The Camp Wyonegonic flotilla graces Moose Pond, beneath Pleasant Mountain. The camp (originally located on Highland Lake in Bridgton) was founded in 1902 by the Hobbs family and is today the oldest continuously operated camp for girls in the nation. (Camp Winona, for boys, farther up the shore of Moose Pond, was founded by the Hobbses in 1908.) The proliferation of camps for boys and girls beginning in the early 1900s provided canoe builders with a welcome important market, the amusement park canoe craze having cooled off with the replacement of the livery canoe (for young couples’ canoodling) by the back seat of the automobile. Camp Wyonegonic’s grand fleet features what appears to be a 34-foot Old Town war canoe with one adult and twenty-two paddlers aboard, double-ended guideboats, and two sailboats of inland lake heritage and pre-World War II vintage. It seems likely that this photo dates from the 1930s.

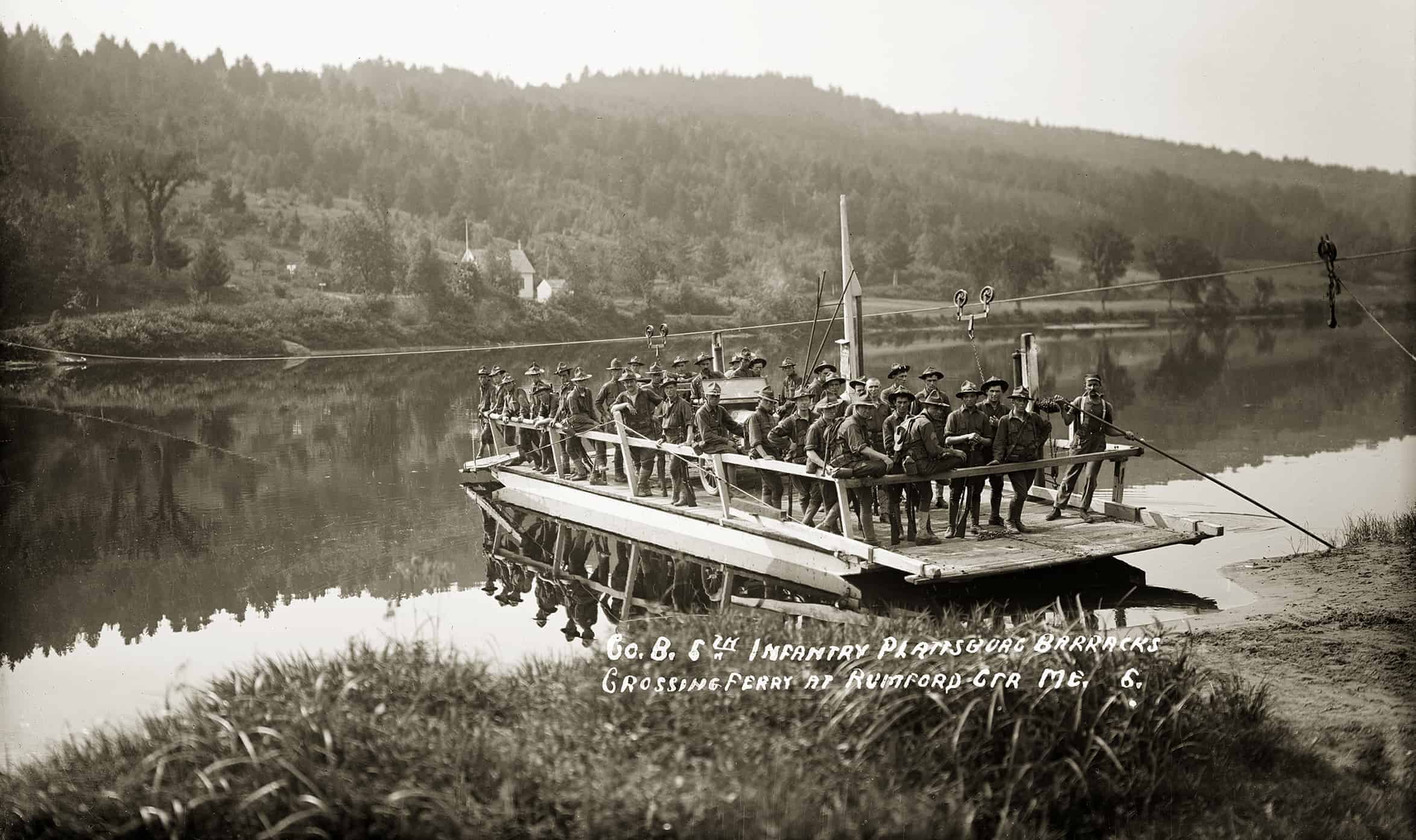

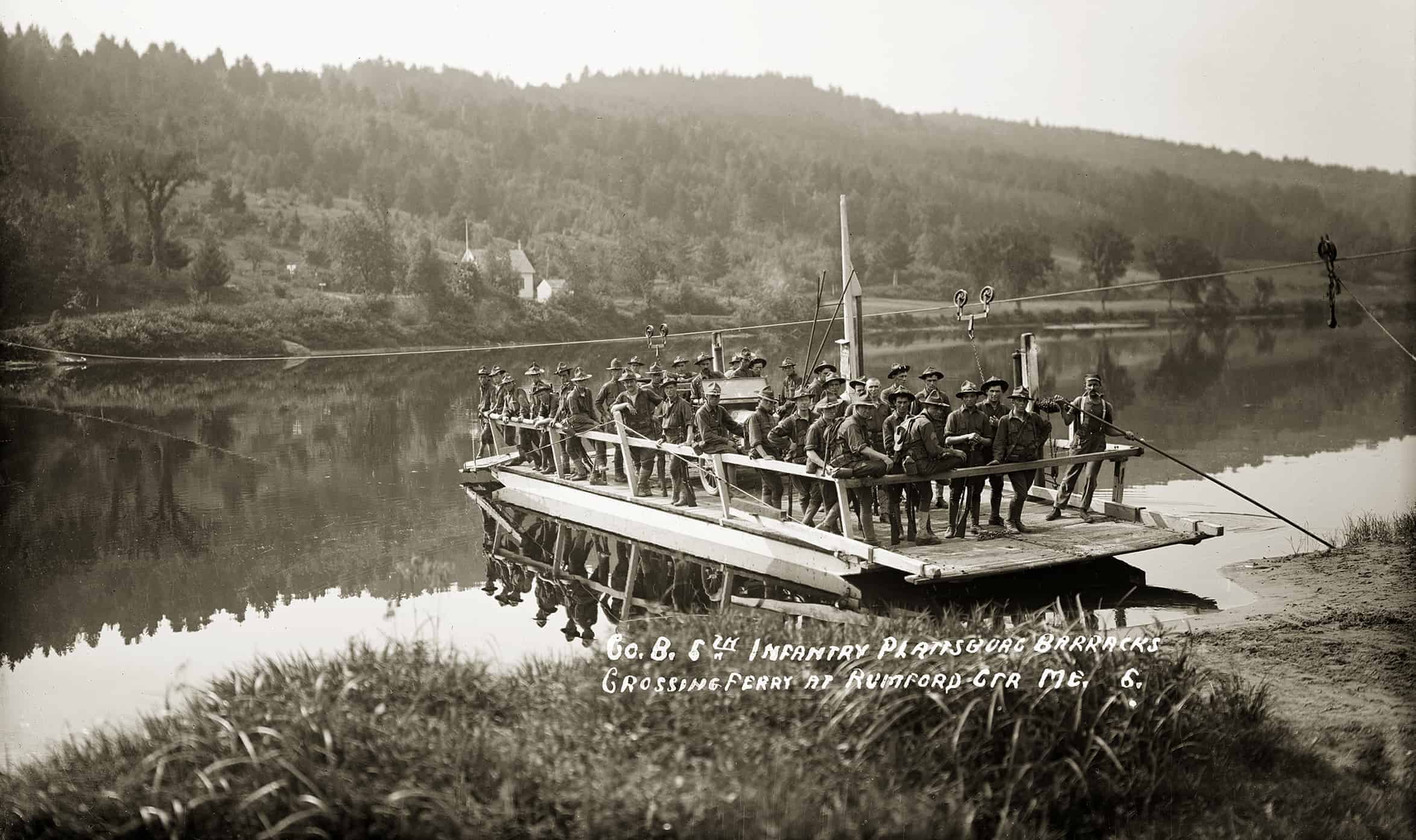

Rumford Center Ferry: The Rumford Center ferry, one of a number of ferries once crossing the Androscoggin, here serves, in effect, as a prototype landing craft transporting members of the 5th Infantry Regiment. We know that the river is flowing from right to left because the trolleys on the cable had to be rigged on the ferry’s upstream side. Chains from the trolleys ran through a pulley on the deck and up to cranked winches. At the outset of a passage the chains were adjusted so that the “bow” was angled upstream, causing the current to propel the scow forward. Two leeboards lowered on the upstream side increased the water pressure. The cable was adjusted to the river height by a capstan. As vital public conveyances, ferries were closely regulated, particularly when running between towns or counties, and were also protected from competition. Traditionally a ferry was summoned by the would-be customer blowing on a communal tin horn. The 5th Infantry Regiment had been very active in the Indian wars but did not see combat in the Spanish American War or World War I. At some point, possibly right after the World War, the 5th was attached to the inactive 9th Division and relegated to garrison duty at Fort Williams, a Cape Elizabeth. Here, they appear to have captured the EIC Model T. The last ferry to operate on the Androscoggin, at Rumford Point (upstream from Rumford Center), was replaced by a bridge in 1955. (MoG page 81)

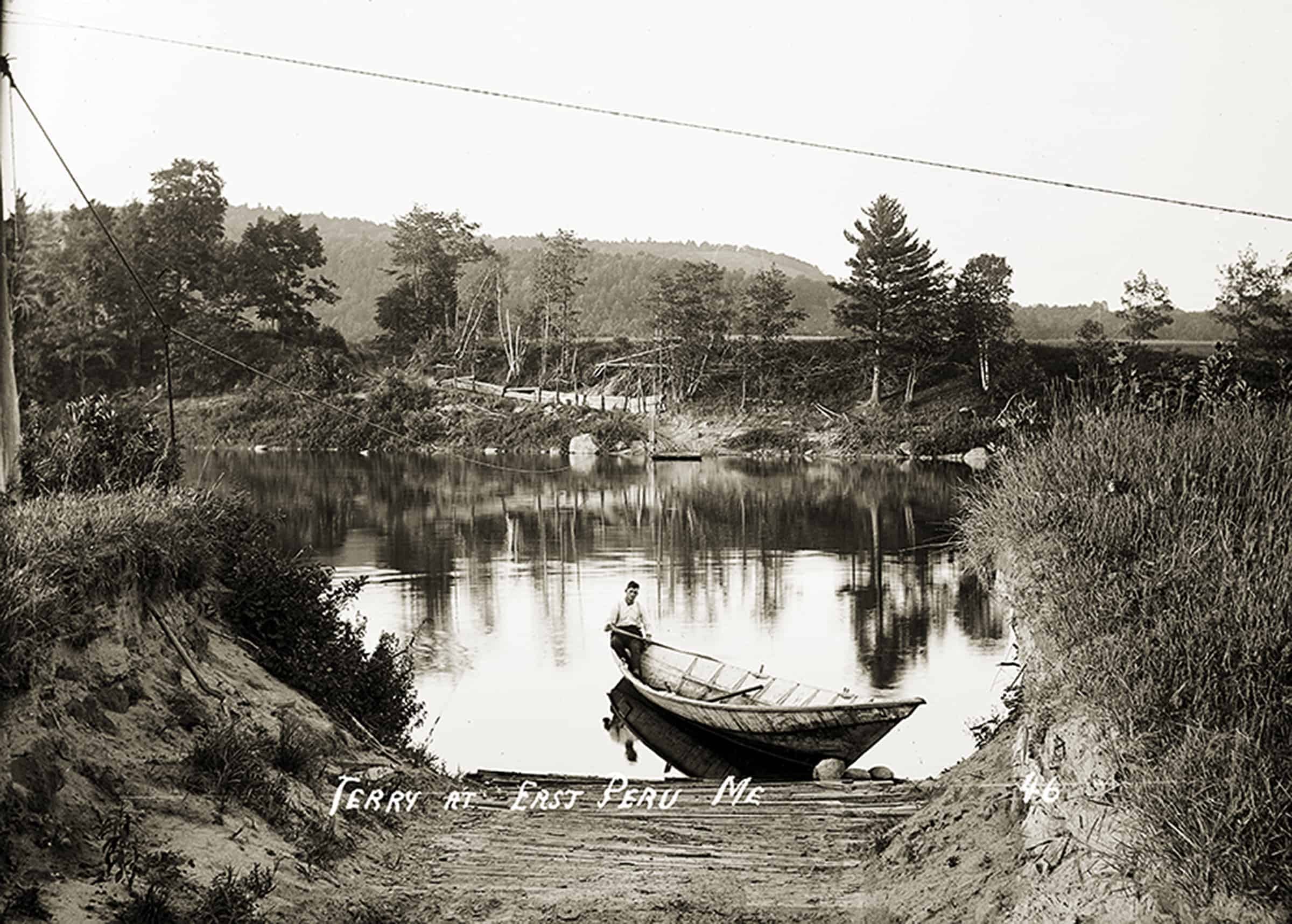

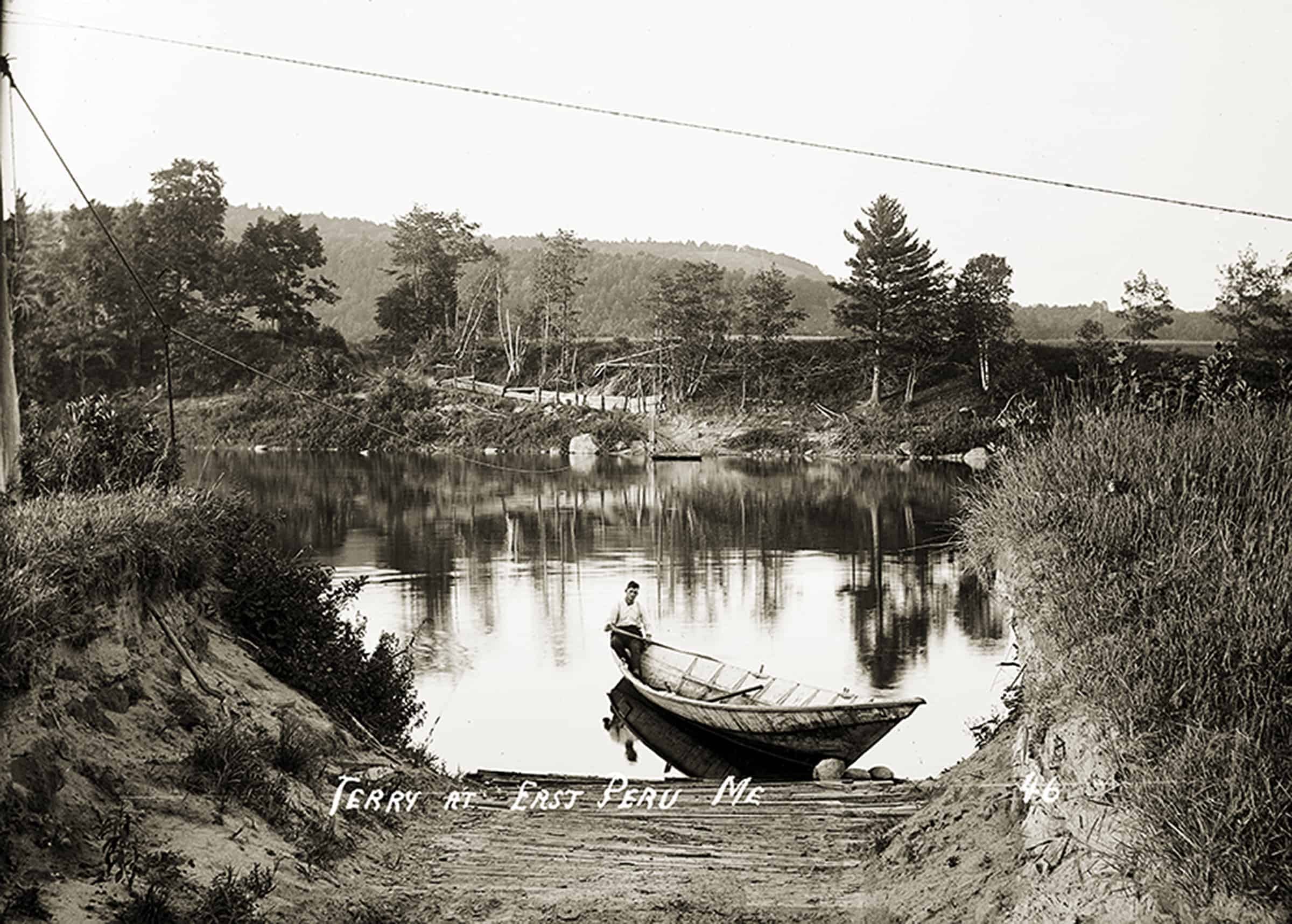

East Peru Ferry: This private Androscoggin River ferry crossed between East Peru (foreground) and Dixfield. The owner and ferryman, William Paul, is paddling a river driver’s bateau—perhaps it had been damaged during a drive, abandoned, and was then repaired by Paul. Paul’s scow, used for his team and wagon, may be glimpsed across the river—the steel cable, which tethers the scow on its crossings, is seen at left. Paul owned a sawmill in Dixfield that produced spool stock, which he ferried across the river to the East Peru station of the Portland & Rumford Falls Railroad. (MoG page 82)

Pulp Boom: At Ripogenus Dam, on the West Branch of the Penobscot at the lower end of Chesuncook Lake, we see a boom of pulpwood, which will be sluiced over the dam. Built in 1916 by the Great Northern Paper Company, Ripogenus was one of the world’s largest reinforced concrete dams. The turn of the century saw vast changes in the North Woods as the fast-growing pulp and paper industry, backed by massive out-of-state capital, rolled over the old long-log establishment. The Great Northern, from its newly built city of Millinocket, ruled some two million acres of forestland with remarkable organization and ability. Unchanged was the reality that wood harvesting was primarily a transportation business, and water was the chief mode of transport in Maine. The postcard caption not withstanding, the boat, GNP No. 3, is not towing the boom. The boom was towed down the twenty-eight-mile-long lake by the splendid 91-foot-long diesel tug West Branch No. 2 or its side-wheel predecessor. Both, of course, were built on the lake shore. (Transporting West Branch’s thirty-ton engine to the lake was a major task.) In 1927, from May 21 to July 27, West Branch, in its first season, delivered fifty-one booms—a boom contained up to 5,000 cords—of pulpwood cut the previous winter. Most pulp was driven to the lake by way of streams; some traveled 120 miles by water to Millinocket. GNP No. 3 may be one of the larger diesel-powered members of GNP’s fleet of “boom jumpers,” which, at flank speed, slid over boom logs on their flat bottoms. The propeller was caged.

Portage: A steam-powered log hoister, mounted on a scow on Portage Lake, is employed “shingling,” or stacking, logs (probably spruce) for the Portage Lumber Company. The mill began operations in 1914, well timed to take advantage of rising lumber prices caused by the war in Europe. The lumbering business was essentially a transportation business. Large quantities of supplies had to be transported into the woods, and logs had to be transported from the woods to mills—and the lumber produced by the mills then had to be transported to markets. For many years, only the extensive networks of waterways—rivers, lakes, streams—by which pine and spruce logs and pulp wood could be driven made logging in much of Maine’s vast woodlands possible. Railroads changed the equation and also spurred the utilization of hardwoods. Before the construction of the Bangor & Aroostook Railroad’s Fish River line, which made the construction of this and other mills feasible, logs landed in Portage Lake were driven north, down the Fish River system of streams and lakes to the St. John River, then south over Grand Falls to be sawn by mills at St. John, New Brunswick. The railroad upset the old order. (MoG page 119)

Schooner David Cohen: This is launching day for the four-masted schooner DAVID COHEN at the Pushee Brothers yard in Dennysville. Among the 330 or so Maine-built four-masted schooners, the COHEN was a rarity in that she was fitted with two oil engines. She was also among the very last, sky-high wartime shipping rates having briefly inspired a revival of wooden shipbuilding. In 1919 the Pushees launched another four-master, the ESTHER K. The cheerful crowd has arrived by train, team, and hundreds of autos. The Pushees had never built so large a vessel and proudly have her fully rigged, with sails bent and bunting snapping in the celebratory breeze. After Miss Wilhemina Pushee christened the schooner with roses and lilies, the COHEN made a satisfactory plunge into the bay, leaving emptiness where she long had dominated the scene. Before her completion, the COHEN’s building contract had passed from her namesake, a New York shipbroker, to another New York firm. Due to the glut of tonnage after the war, in 1921, the COHEN, which cost $140,000 to build, brought but $10,200 (without engines) at a marshal’s sale. David Cohen may have been a party to her purchase.

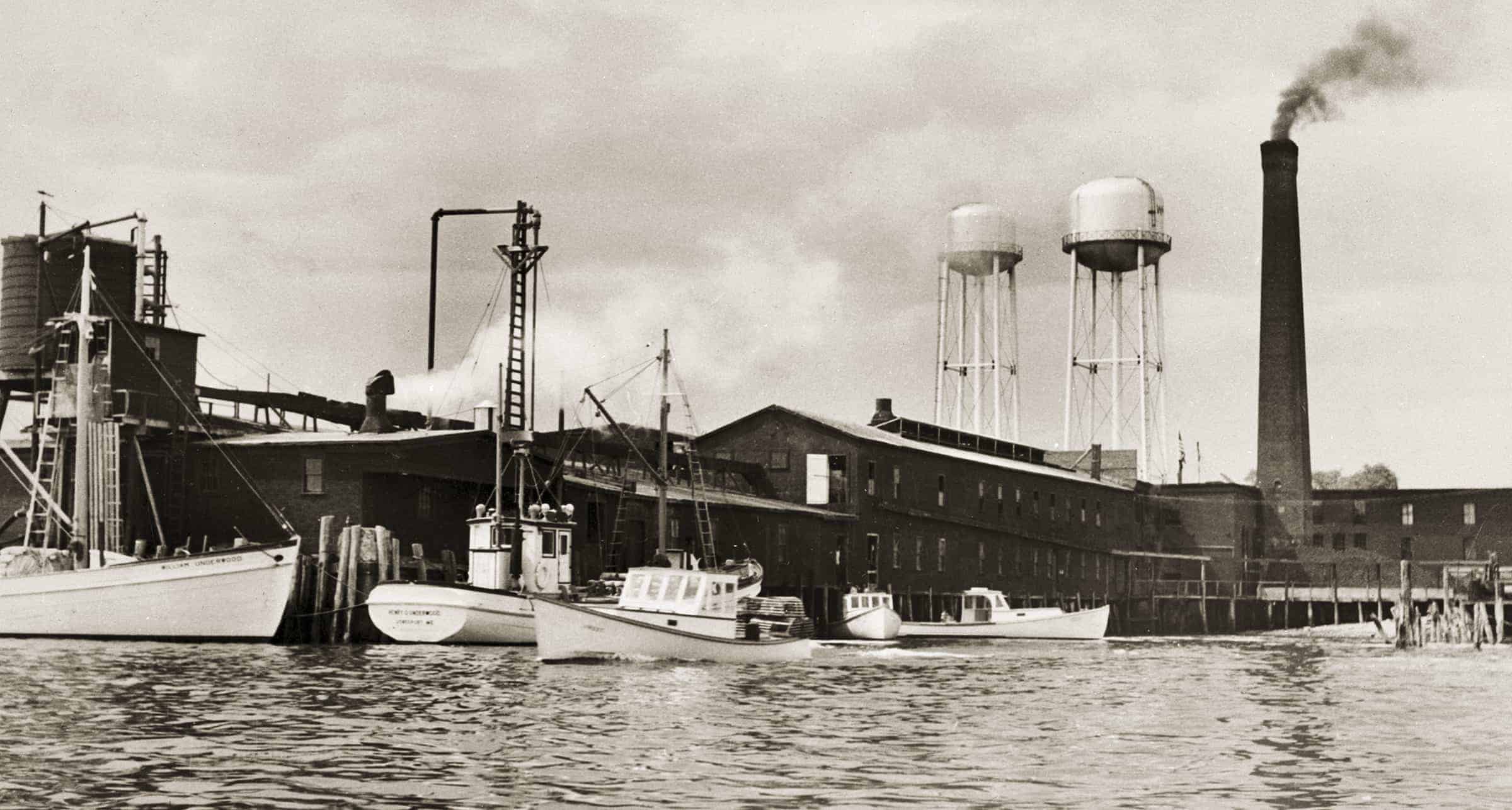

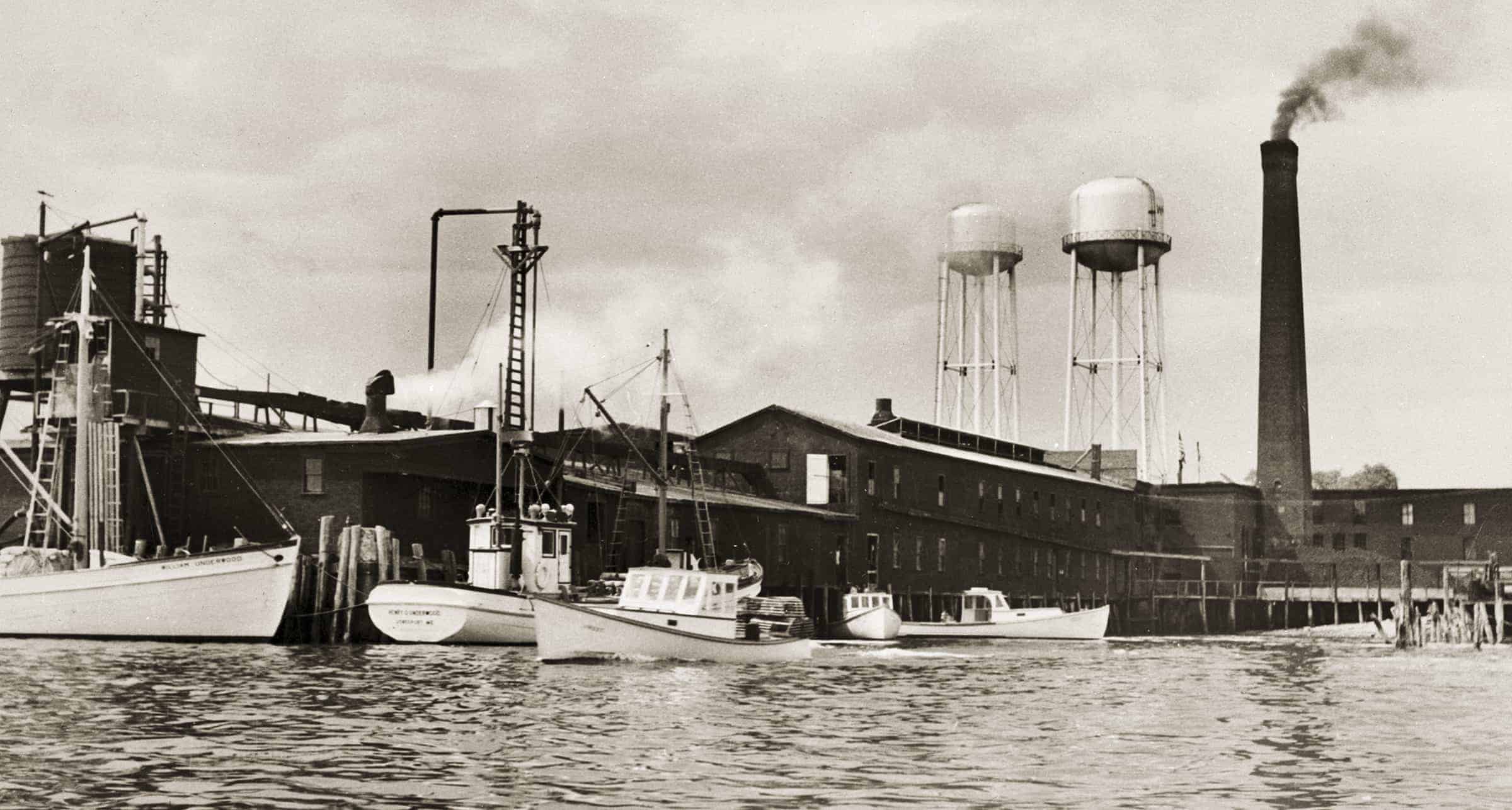

Sardine Factory: The William Underwood Company sardine factory, said to be the world’s largest, on Moosabec Reach, is shown here circa early 1950s. Built in 1900, it was always considered to be an industry leader. Not in view is the large, attached “Tenement House” for workers; a ferry brought workers from neighboring Beals Island. At left we see the bow of the 1941 sardine carrier WILLIAM UNDERWOOD, and to the right of it the stern of the 1949 carrier HENRY O. UNDERWOOD. Splice them together with your eye and you have a classic sardine carrier, which were among the handsomest and easiest-driven of all power vessels. Carrier skippers were master pilots, and even though the boats worked among ledges and shoals on dark and foggy nights to reach “shut off” coves where a school of small herring had been trapped, they were said to be insured at the lowest of rates. The smaller boats are Jonesport-model lobster boats, also timeless classics. They have been receiving fish cuttings with which to bait their traps. Wartime over-expansion, foreign competition, the growth of snack foods, declining numbers of fish inshore, and changing public tastes put Maine’s sardine industry into a fatal decline after the early 1950s. In 1962 the Jonesport factory closed. Happily, the WILLIAM UNDERWOOD is today undergoing restoration for a new life as cruising yacht. (MoG page 152)

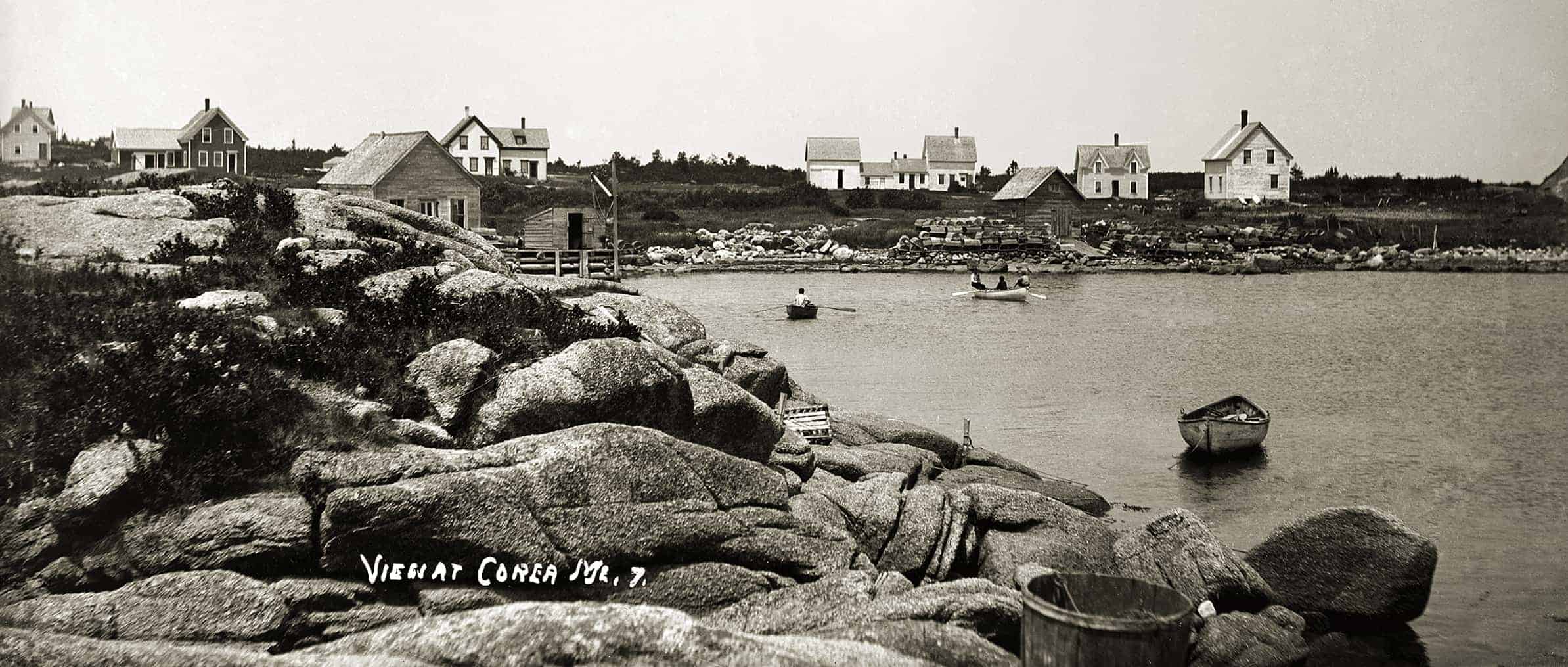

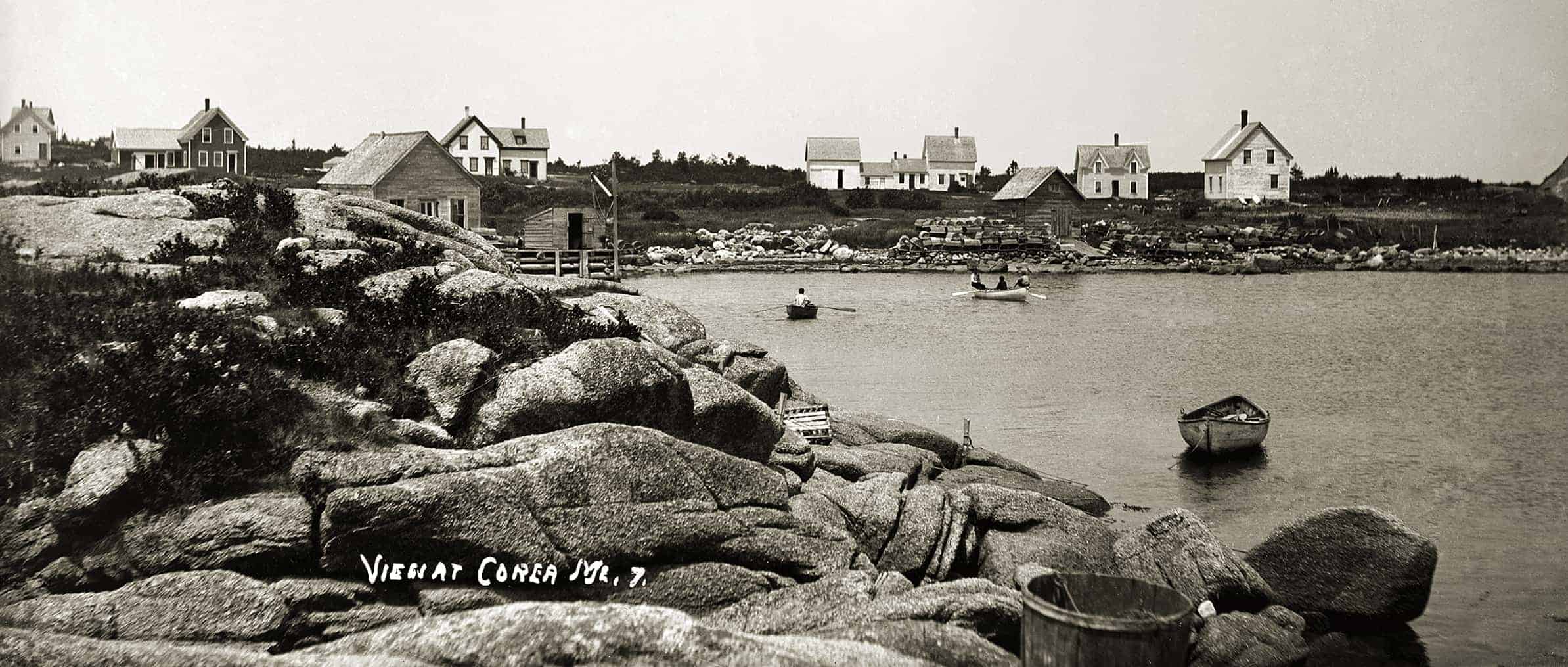

Corea Harbor: This view of Corea Harbor shows houses on the Crowley Island Road. The two houses on the left belonged to Daniel Young and Ephraim Crowley, respectively. Both Young and Crowley were descendants of settlers. In 1843 Captain Nathaniel Crowley married Isabella Young of what was then Indian Harbor. They had fourteen children whose descendants comprised a significant portion of the local population. These two houses have survived, but the other buildings have all since burned. Half of a sugar hogshead is at lower right. Molasses and sugar from the West Indies arrived in large hogsheads which, when halved, found many uses in fishing villages. The boats are double-ended peapods. While another image shows half a dozen Friendship sloops and a couple of powerboats at moorings, the village of Prospect Harbor, with a sardine factory, was the center of maritime activity in Gouldsboro. (MoG page 154 & 155)

Ellsworth: At the head of navigation, and with water powers at Ellsworth Falls, Ellsworth was long the sawmilling and lumber-shipping town for the Union River watershed. In the 1870s and ’80s, the chief lumber customer was booming Bar Harbor, and ever since, especially after the rise of the automobile, Ellsworth and Bar Harbor have been closely linked economically. By the late 1800s the chief lumber product being shipped out of the Union River was barrel staves for Hudson River cement plants. We are looking toward Bridge Hill, on the west side of the river, circa 1910–15. The building at center is the foundry for Ellsworth Foundry & Machine Works. In 1913 the company manufactured marine and stationary engines and operated both a marine railway and a garage. The foundry, along with other riverfront buildings, was destroyed in the Great Flood of 1923. The Great Fire of 1933 destroyed a large portion of the business district on the east side of the river. The roof of the Masonic Hall is seen beyond the foundry, at center. The spire of St. Joseph Catholic Church on Bridge Hill is in the background. Three motor launches and a rowboat float in the foreground. (MoG page 162)

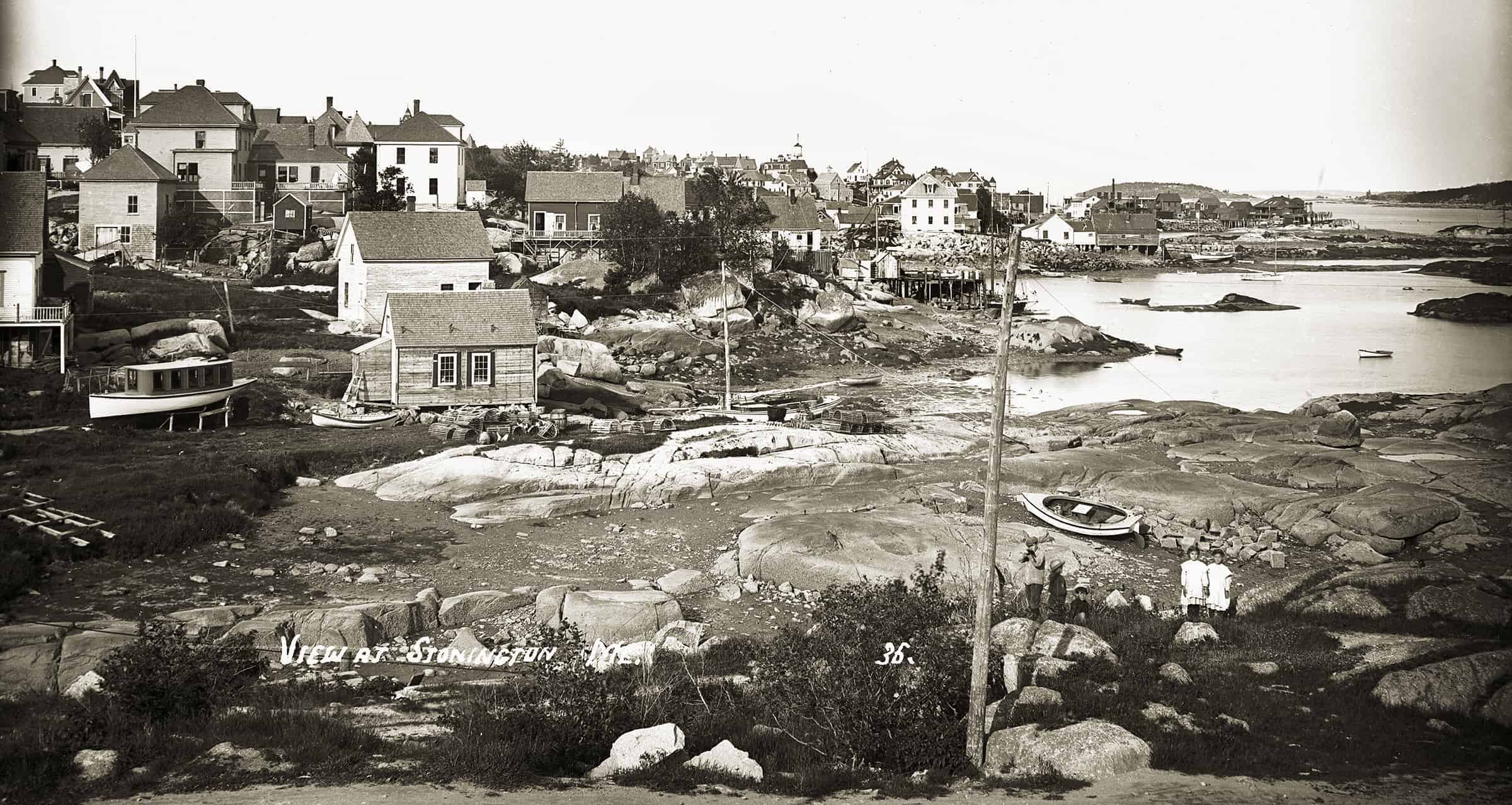

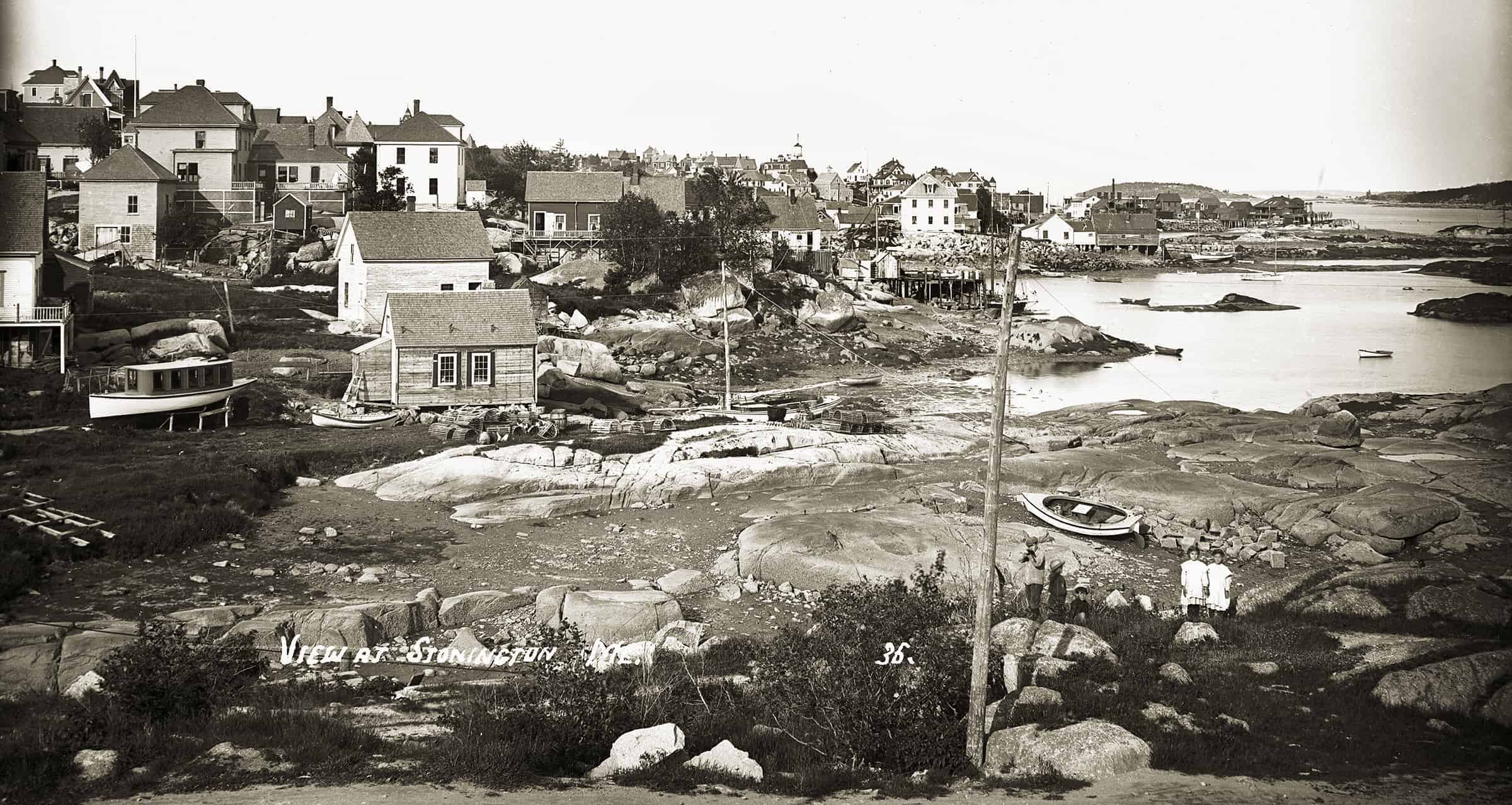

Stonington: The tide is low, the year probably circa 1915. The five children at lower right make this a successful image rather than a lifeless “neutron bomb” villagescape with everything intact but nary a soul in sight. Deer Isle’s commercial ties were then with Rockland, linked by steamers; after the bridge to the Blue Hill peninsula was built in 1939, Ellsworth became the place where islanders “traded.” Formerly a small fishing village known as Green’s Landing, Stonington was incorporated in 1897, reflecting its booming granite industry. From about 1910 its population declined, matching the fading fortunes of the granite business. However, the big quarry on Crotch Island, just across the Deer Isle Thorofare from the village, remained quite active until World War II. The granite industry attracted immigrant workers, including many Italians who were mostly single men, making Stonington a lively place on Saturday nights. Thin-soiled Deer Isle had a long tradition of fishing and seafaring. Beginning in the late 1800s many island men “went yachting,” manning the “gold-plated” floating status symbols of the wealthy. Two America’s Cup defenders were crewed by Deer Islanders who displaced the regular Scandinavian “squarehead” racing sailors. Although both defenses succeeded, the practice was not continued, supposedly because the independent islanders were said to consider orders to be suggestions. “Going yachting” continued into modern times. (MoG page 168)

South Brooksville: Friendship Sloop The sloop LULA MARION at Bucks Harbor, at the western end of Eggemoggin Reach, in South Brooksville, a village in the town of Brooksville. Of an iconic model now collectively called “Friendship sloops,” the LULA MARION was in fact built at Friendship in 1899. Friendship’s most prolific builder was Wilbur Morse, and the LULA MARION bears all the hallmarks of a Wilbur Morse sloop. Most sloops fished or lobstered, but the LULA MARION’s owner, Melvin D. Chatto, owned the Bay View Hotel (which was affiliated with the adjacent Gray’s Inn, the two arks standing on a rise above the steamboat wharf), and no doubt the sloop, skippered by a local fisherman, also took out sailing parties. Indeed, it would appear from other photos that she was one of three Friendships so employed. Chatto, a big fish in a small harbor, was also the president of the Bucks Harbor Granite Company and a state senator. The sloop is lying at what locals still call the pogy wharf.In 1912 and 1915 the LULA MARION, sailed by Joe Ladd—presumably the local fisherman who took out the sailing parties—won the annual Eagle Island sloop race. In 1917, possibly marking her sale to a fisherman, an engine was installed. A few years later she disappeared from the merchant vessel list—perhaps she was sold as a yacht or fell apart or even blew up from gas fumes in her bilge. It happened. (MoG page 171)

Boat on Truck: The viewer is free to speculate about the backstory of the boat on the truck at Blake’s Point on Cape Rosier, in the village of Harborside, in the town of Brooksville. It may help to know that Maine did not start requiring the display of registration numbers on motorboats until 1960, nor would Maine registration numbers begin with “K.” One possibility is that the boat belonged to a summer person from out-of-state and was shipped by rail to Ellsworth. Of course, it did not arrive on a flatcar with the canopy rigged and flags flying; they would have been installed preparatory to the boat’s celebratory arrival in Brooksville. According to Maine auto historian Warren Kincaid, the “canopy” is the top of a pre-1923 touring car and is typical of a 1915 or so Model T Ford top. Early truck manufacturers used many of the same parts from the same suppliers, making identification difficult, but in this instance the radiator has mounting brackets typical of Sterlings and Packards, circa 1910–14. The electric lights were likely added later; they became popular around 1915. (MoG page 172)

“Bangor River:” Traffic on the Penobscot, or “Bangor,” River. The Eastern Steamship Company’s Boston-to-Bangor steamer BELFAST, headed downriver, is passing the Ross Towboat Company’s tug WALTER ROSS, which has a handsome three-masted schooner and two small two-masted schooners in tow. The twisting twenty-four miles from Bangor to Fort Point, at the head of Penobscot Bay, was always challenging, particularly for the great fleets of lumber vessels that once made the passage under sail. (Fort Point is where tows of smaller schooners were made up; big four- and five-masted coal schooners were often met by a tug in the lower bay, even off Monhegan.) The more-than-twelve-foot tidal range at Bangor is the greatest of any place on the coast west of the Bay of Fundy. During the booming pine lumber days before the Civil War, over three thousand vessels arrived (and then, of course, departed) from Bangor during the seven-month shipping season. Even in the 1880s, when spruce lumber and ice were major exports, fifteen hundred arrivals might be expected. Sailors, loggers, longshoremen, saloons, and bordellos made for lively times, and the tough Irish cops patrolled in pairs. In the early 1900s there were days when the waterfront still resembled its palmy days, but by 1920 the waterfront was all but dead, save for the daily Boston steamer and the odd schooner and barge. (MoG page 174)

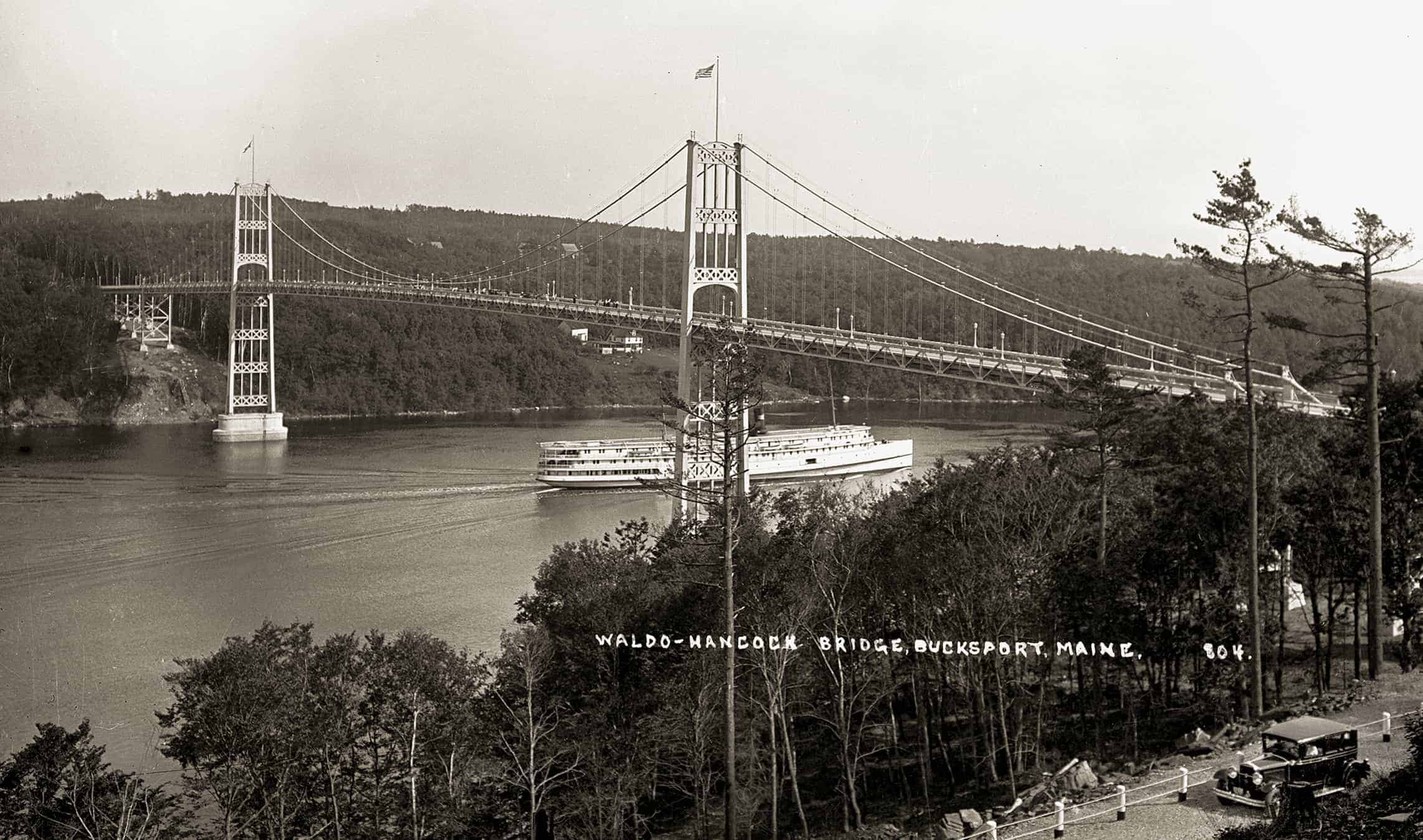

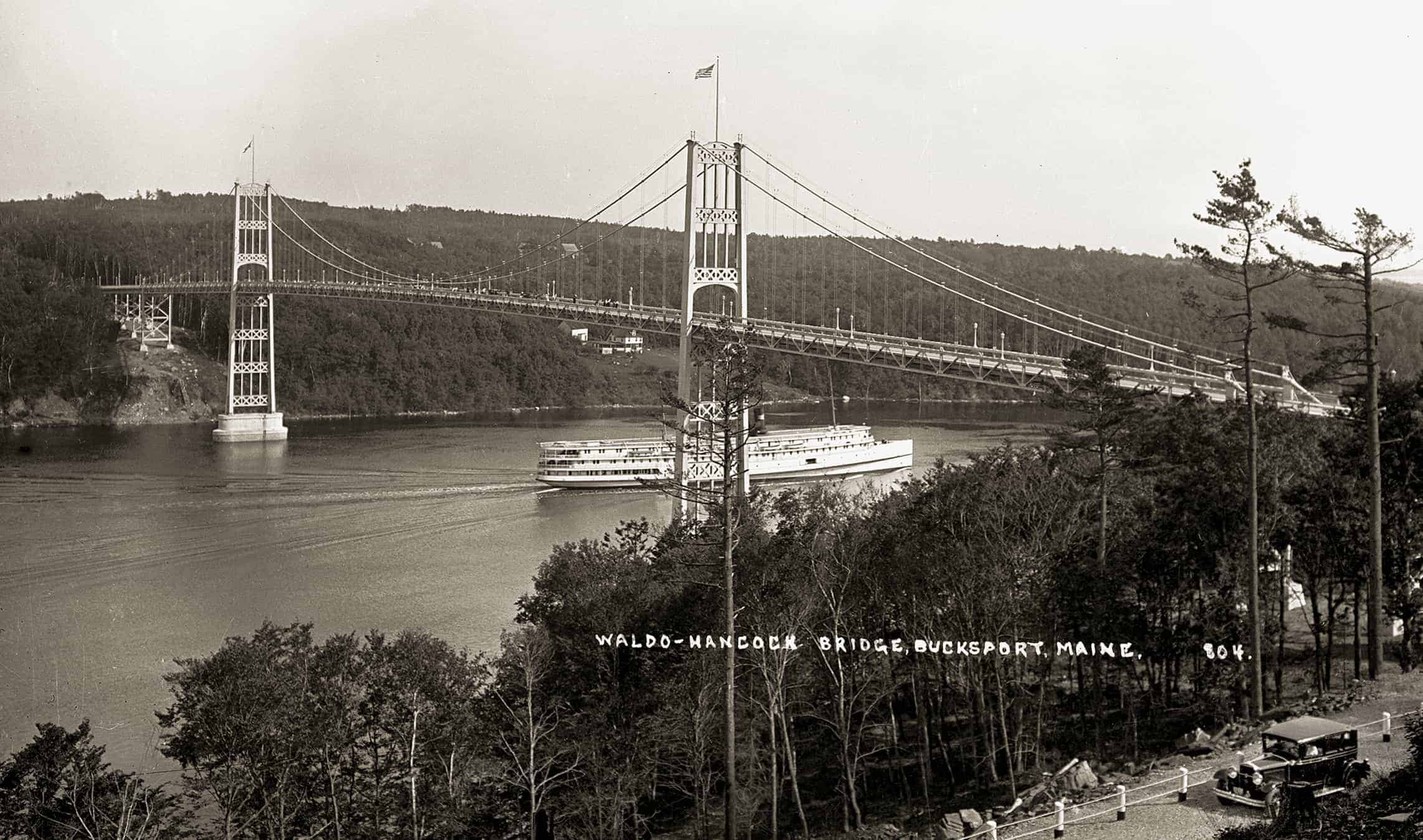

Waldo-Hancock Bridge: On opening day for the new Waldo-Hancock Bridge over the Penobscot River, connecting the town of Prospect with Verona Island, one of the Boston-Bangor steamers (BELFAST or CAMDEN) passes beneath. At lower right lurks an automobile, whose tribe’s explosive popularity created the need for the bridge, and which, in four years, will end the 102-year history of Boston-Bangor steamer service. The steamer, bridge, and auto each represented state-of-the art technology when built. The Bath-built 335-foot steamers, BELFAST and CAMDEN, were the first steel-hulled, screw-propelled vessels and the first true seagoing vessels employed on this route. They were also two of the first three American-built turbine-powered vessels. While flammable, they were not the ever potential floating conflagrations they replaced. The bridge was among the earliest to employ pre-stressed wire strand cables and the Vierendeel truss later used in the Triborough and Golden Gate bridges. It also cost well under budget, permitting the construction of a second bridge between Verona Island and Bucksport and a road route across the Penobscot twenty miles downriver of Bangor. The Bucksport–Prospect ferry, which the bridges replaced, was a scow that had long inspired both rage and ridicule.

* * * * *

You can purchase an autographed copy of Maine on Glass directly from Penobscot Marine Museum at the list price of $29.95, or a discounted one without the autographs from Amazon.com (which, by the way, shows the book with a five-star rating). Believe me, it’s a treasure!

Individual prints of any of these photographs can be ordered from the museum. Contact Kevin Johnson, PMM Photo Archivist.

. . . sign up to the right to get immediate access to this full post,

plus you'll get 10 of our best videos for free.

Get Free Videos& Learn More

Join Now!!for Full Access

Members Sign In

You can leave a comment or question for OCH and members below. Here are the comments so far…

David Tew says:

I would have liked to have been there to se the steamer Castine leave Isleboro’s Smith Wharf ferry landing. The onshore breeze looked pretty stiff and she lay broadside to it, but doubtless it was a trick the captains knew how to finesse.

Alden Reed says:

Southport Steamers: The location in the photo is known as the Upper Southport Landing. The building on the far left still remains and has been converted to a house. In the 19th century, a bridge from this location crossed over Townsend Gut to Oak Point on the mainland. In the background is the Isle of Springs.

“The nineteen hundred teen years marked the height of the steamship era. Four steamers, the WESTPORT, the SOUTHPORT, the WIWURNA, and the NAHANADA, operated on the Bath-Boothbay Harbor –Christmas Cove run. The ISLANDER daily made a round trip between Augusta and Boothbay Harbor, and the WINTER HARBOR [which besides passengers and freight carried the mail] made two round trips daily between Boothbay and Wiscasset. All these ships stopped at the Isle of Springs… “On the ship, as she neared the wharf, a crew member would go through both decks, calling ‘Landing on the upper deck,’ or lower as the case might be, to notify passengers where to disembark…. During World War I, [a serviceman] from the Isle of Springs served on a destroyer which entered Southampton Harbour in England for supplies. “….[I]t was so full of ships one had to raft up to another which was rafted to another. [The serviceman] looked at the ship to which they were rafted and thought he recognized it; he checked through the camouflaged paint, and sure enough it was the SS SOUTHPORT….which had crossed the Atlantic and was being used to ferry troops and supplies across the English Channel.” (Excerpted from Recollections by A.S. Hutchinson, Isle of Springs, Maine, 1983).

Alden Reed says:

Maynard, that motorboat on the truck looks like a Hand-V-Bottom. It may possibly be Hand’s 20-ft Skilligalee model (Design No. 337 High Speed Runabout drawn about 1914). Registration numbers and electric running lights came in the early 1920s, the ME prefix came in about 1960.

My understanding is the wait to cross the Kennebec on a car ferry at Bath/Woolwich got even longer if you happened to be in line behind a fuel truck because it was required to cross by itself.

Peter Brackenbury says:

Modern Digital photography is a wonder and an incredibly convenient tool, however, these photos are so beautiful to me knowing the incovenience and the process behind them. Not to mention their historic value and the way they capture a place and time. Beautful!

David Tew says:

Thanks for reminding me about this book. It’s a storehouse of insight and history.

Ben Fuller says:

We should figure out how to add comments to individual photos, material that Bill couldn’t get in, taking advantage of our ability to zoom. For example for LULA MAY if you zoom in you’ll see barrels loaded on the sloop, fish, bait or lobster. To the left a couple of knickerbockered lads look down on a gent in a skiff. To the right is the stern of an upside down livery boat. With the tide out the photographer could walk down the beach a little and set up his tripoded glass plate camera.

Maynard Bray says:

Hi Ben, Any information submitted as a comment stays with the post and, if the system works as it’s set up, will eventually be fed back to the museum’s database. It’s rather ungainly at this stage and we’ll work on streamlining. Each of these PMM photos, perhaps, should have its own feedback loop. Anyhow, you raise a good point and I hope that anyone who views these images and has more information to share will come forward and leave a comment just as you did.

Ben Fuller says:

Most of these pics deserve close attention to look for the details; The Carvers Harbor photo shows an interesting paint job on one of the pods, one Friendship loaded with traps but no sail at all. Another with a sail shows the greasy exhaust residue of a one lunger.

The pod in the Corea pic was captured better in another photo that focuses on it. You’ll see three in it, young fellers larkin about and maybe posing I think. http://penobscotmarinemuseum.pastperfectonline.com/photo/773E77EE-DB45-4B64-A794-855423675570 (LB2007.1.105075 ) Anyone see that nice torpedo stern launch?

Claas van der Linde says:

Thanks, Maynard, for this post. This is really a wonderful book, both in terms of the photos and in terms of Mr. Buntings great captions. This was my summer book on the boat sailing in Maine, always a couple of pages in the morning in the cockpit or a chapter in the evening below deck. A much recommended book!