This is about sailing and giving, both of which OCH Guide, Nat Benjamin, excels at. In CHARLOTTE, a wooden schooner that Nat designed and built for himself and his family, Nat takes us on a winter voyage to the south coast of Haiti where he delivers a boatload of supplies to a local orphanage, and learns about the people who live there. Nat’s booklet, Passage to Haiti, which had limited circulation, compelled us to create a Guide Post so that OCH members could read about CHARLOTTE’s voyage.

Part 1 of this two-part series gets us, by water and in winter, from New England to Haiti via Bermuda. Part 2 will cover what a Haitian coastal village is like.

At 1000 hrs on December 10, 2014, 13 days after our snowy departure from Martha’s Vineyard, MA, we sighted the steep verdant mountains of Hispaniola rising from the tropical sea, piercing the hazy cerulean sky. Landfall is a momentous occasion aboard an ocean sailing vessel. It is a welcome reward following the continuous cycles of life underway: standing watch day and night, and observing the constant changing shades of water and sky on the far horizon. All hands shared in the duties required to manage the delivery south: tending sail and taking the helm, navigating, cooking, cleaning, and mending as we drove our 50’ schooner, CHARLOTTE, through the vagaries of wind and ocean–-living and working together with the common goal of arriving safely at a distant land. Landfall is a time for celebration and gratitude.

However, the journey was not yet over. After sighting this majestic island 50 miles to the south we now had to approach the Windward Passage, sail southwest along the western coast of Haiti to Cap Dame Marie, then head east to our final destination: a small island called, Île-à-Vache.

With our eyes focused on this new attraction, we arrived at the Northwest coast of Haiti at twilight. Close reaching a half-mile or so offshore, we observed, as if through an ancient lens, the inaccessible rugged terrain plunging to the sea, shrouded in a smoky, mysterious veil. Casting and hauling nets from locally hand-built working sail boats, dozens of fisherman waved pleasantly to us as we slid silently along from one coastal village to the next. As the light faded, I stood further off shore to avoid collision with these capable but primitive, unlit and engineless watercraft. Haiti became black as the surrounding night save for an occasional fire on the beach or in the hills above, and the island’s distant mountainous outline backlit by a waxing moon. We had sailed into another time zone of centuries past—a quiet, still, dreamlike place.

A moderate easterly katabatic night wind slid down the high volcanic slopes and across the water, making our way south through the Windward Passage between Haiti and Cuba a pleasant reach with sheets eased on an easy sea. Shortly after midnight we rounded Cap Dame Marie and set our course for Île-à-Vache, some 20 nautical miles to the ENE. The cooperative breeze backed a few points to the north, allowing us to make our heading in one tack, and by 0300 we had rounded up in the lee of a pristine uninhabited cove and set our anchor in the white sand 20 feet below in clear, moonlit water. With sails stowed and CHARLOTTE finally at rest, all hands walked about the deck in quiet conversation observing this wonder of the natural world unchanged by man. For all of us, this was a landfall like none other.

Since my first visit to Haiti in 2011, I’ve had a strong desire to return. At that time, we sailed to the north coastal town of Labadie where my friends Ted Okie and Tracy Jonsson were spending the winter while Tracy documented the classic and crumbling French colonial architecture in Cap Haitian for her master’s degree in historic preservation. My shipmates and I were struck by the kindness and generosity of the people, their good nature, work ethic, and resolve in the face of abject poverty and little opportunity. But there was a much deeper feeling that seemed to penetrate the ground itself—powerful, mysterious and soulful: a magnetic pull to the visceral texture of this Afro- French West Indian culture.

Stumbling around the Internet one winter evening in 2013, I noticed the “Free Cruising Guide To Haiti” online. I contacted the author, Frank Virgintino, and, as so often happens on our ever shrinking planet, we re-connected 30 years after he had sold a large quantity of bronze hardware to our boatyard (at ten cents on the dollar). When I informed Frank that I wanted to return to Haiti on CHARLOTTE, he made it very clear that if we liked the north coast we would love the south. “You must sail to Île-à-Vache,” he implored.

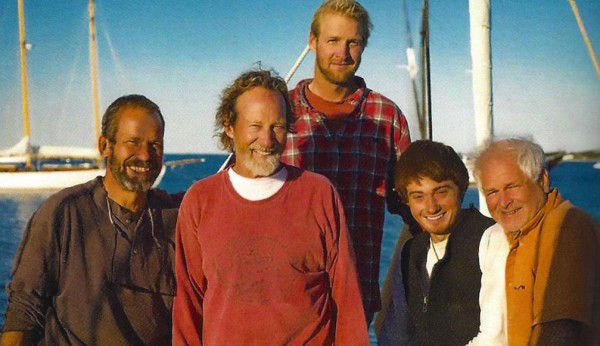

Photo: Alison Shaw

Taking his advice, I sent an email to his Haitian friend, Sam Alteme, in Kai Kok, the little village in Port Morgan harbor. Sam responded quickly and informed us of the various needs of his community, the impressive work of Sister Flora and her orphanage, and what we might bring to Haiti aboard CHARLOTTE. My wife, Pam, reached out to the database of her non- profit organization Sense of Wonder Creations.org and our boatyard office manager, Angela Park, notified the friends of Gannon and Benjamin Marine Railway of our intentions. Virginia Jones enlisted local fishermen to contribute a generous supply of hook-and-line fishing gear, and before long we had an enthusiastic band of donors bringing clothes, books, games, art materials and cash to be delivered to the orphanage. I collected bags of old sails to supplement the fishing gear destined for the Haitian watermen as well as used tools and rigging for the local boatbuilders.

By late October 2014 CHARLOTTE was laden with a cargo liberated from America’s dumpsters, mostly, and stowed below deck in every available space, including the bilge.

Preparing for a December offshore passage from New England to the lower latitudes requires careful examination of your vessel and its multitude of parts, all the way from the masthead to the bottom of her keel. A long “to do” list was prioritized and, with the help of my companions, the work was accomplished over several weeks with only a few minor projects left for another time.

Essential items for the journey included nautical charts, plotting instruments, cruising guides, nautical almanac and sight reduction tables for celestial navigation, sextant, courtesy flags for every country we intended to visit, pelagic bird and tropical fish guides, tide books, tackle box, first aid kit, sail repair sewing-and-rigging bag, spare parts for the engine, water pumps and other mechanical/ electrical equipment, backgammon board, dominoes, playing cards, music, and don’t forget the toilet paper. Diesel fuel, potable water, propane for the galley stove and the provisioning of staples of food, rounded out the commissioning task.

We hauled our wooden rowing tender aboard, using the fisherman halyards, and lashed it securely to the stanchions and deck house grab rails along the port side deck.

Jack lines were stretched taught along the deck to provide quick access for clipping in the safety harness lanyards. Lifelines at the rail, foot ropes on the bowsprit, man overboard pole, life ring and strobe light were all tested for sea. I prepared an emergency “go” bag to include the EPIRB, first-aid kit, distress flares, water bottles and some dark chocolate. The life raft was made fast to the cabin top amidships.

Selecting your shipmates is an easy task on Martha’s Vineyard given the vast pool of competent sailors who easily succumb to the lure of mysterious tropical islands and all their enticing possibilities over the alternative to old man winter who grips our northern terminal moraine and its captive inhabitants with such unbridled enthusiasm.

My first requirement was to find a mate who could look after CHARLOTTE when I went back up north. My friend Ian Ridgeway and I had been talking about this eventuality for several years and now the planets were aligned in their proper order, terrestrial bonds were laid aside, and Ian committed himself to the care of CHARLOTTE for the forthcoming five months. Knowing that CHARLOTTE would be in good hands when we were not aboard was a great relief to me and Pam. Ian had started sailing on the 108-foot square topsail schooner, SHENANDOAH on a 5th grade class trip and continued every year, working his way up “thru the hawse hole.” At the age of 24 he became master of the 90 foot pilot schooner, ALABAMA. His knowledge of the sea and the way of a ship, his musical ability, good humor, and gracious nature put him at the top of his game. Without Ian to fill this vital role, we could not have made the voyage.

The Gannon & Benjamin boatyard is also a recruiting station for sailors in a casual, serendipitous arrangement where shipwrights occasionally disappear from their usual place at the workbench to a position aboard a vessel outward bound. Usually, we (the managers) are aware of such departures. To my great relief, Brad Abbott and Zoli Clarke were both willing to abdicate their earthly responsibilities and join the jolly crew of CHARLOTTE, proving once again that no one is indispensible, or, to paraphrase one astute psychologist, “the cemeteries are full of indispensible people.” Brad, our recent partner in the boatyard, has survived previous excursions to the tropics aboard CHARLOTTE as well as on his own 48 foot yawl, AURORA, and brings capable expertise in all aspects of offshore cruising. Zoli, another charter member of the boatyard crew since he received his working papers at age 13, has sailed on CHARLOTTE as first mate and chief maintenance coordinator for six years and he knows the boat in every detail. Both of these men are nimble sailors and know how to cook.

While the weather service continued to advise us to postpone our departure due to a succession of frontal systems producing unpleasant southerly gales, and due to the psychological effect those predictions foster, I decided to take on another crew member at the 11th hour to ease the burden for the rest of us. I called on my old friend Malcolm Boyd the day before Thanksgiving to see if he would join us—a simple request, I thought, and much less alarming than specifically asking him to leave his job and family for an unknown period of time with no pay to go thrash about in the North Atlantic in December. He replied, “When do we leave?” I suggested, “Tomorrow,” in light of the recent and more promising weather forecast. Of course no one wants to leave family and friends, turkey and yams, on Thanksgiving Day and so, weather oracles notwithstanding, we set our ETD for the day after holiday stuffing.

There is a history of migratory sailing vessels casting off from Vineyard Haven when the daylight shrinks to darkness before dinner and the cold north wind begins to moan in the rigging. The 65’ Gannon and Benjamin schooner, JUNO is a veritable commuter to the West Indies, missing only one season in 13 years when Captain Scotty DiBiaso sailed her to Europe for a summer in the Mediterranean. My partner, Ross Gannon, and his family migrated to the islands aboard their 45’ sloop ELEDA for the winter of 2013-14. Rick and Chrissy Haslet have completed two round trips aboard the impeccable ketch, DESTINY and Todd Bassett and Lee Taylor continue to cruise south in their classic yawl, MAGIC CARPET, after sufficient recovery from their previous escapades.Is there a pattern here? Why do we do this?

Rest assured, when the wind begins to howl, the seas build into mountains and toss your precious, varnished cockleshell like a cork in a washtub, and the lee rail beckons for the contents of your last meal, suddenly all those indestructible cast bronze fittings, stainless steel wire rigging, and the basket of boards screwed to frames with cotton string caulked into the seams (i.e. the vessel) begins to take on an esoteric eastern philosophical atmosphere—as in the impermanence of all things—nothing, absolutely nothing, will convince you that this ocean voyaging business is a good idea. But there is no time to dwell on the regrets of the unraveling situation, but rather, deal with the elemental present reality knowing that you are in your right place to keep your vessel and shipmates secure for the duration. Eventually, the storm ends, the sun appears, and the mercifully short memory of the sailor allows us to carry on with impunity.

With those cheerful thoughts forgotten, we set sail on November 28th with a forecast of freshening north wind and snow flurries building to what the old timers used to call a “pleasant gale” from the northwest, or well abaft the beam. The reefed mainsail, foresail and forestaysail provided plenty of canvas to drive CHARLOTTE’s 58,000 pound displacement out of the harbor and fly her along at hull speed up Vineyard Sound with a fair tide past the Gay Head light where we set our course for Bermuda, 650 nautical miles to the south southeast. The first bitter cold night gave way to a blustery sunny day as CHARLOTTE charged southward with all hands adjusting to the rollicking motion and post-Thanksgiving digestive cycles. By the end of the second day, the wind moderated and all sail was set: mainsail, foresail, forestaysail, jib and fisherman staysail.

That borderless river of tropical water known as the Gulf Stream greeted us with leaping dolphins, a welcome of warm air and a favorable current. We shed our winter woolies and set our inner clocks to the rhythm of our watery world. I had set a watch system with two men on deck for three-hour shifts around the clock. A careful record of compass heading, average speed, wind force/direction, barometric pressure, bilge condition, engine hours, battery voltage, sails set and the ship’s position were entered into the logbook at the end of each watch.

The mariner’s mantra is ”constant vigilance.” To let down your guard is an invitation to trouble, and all shipmates must be alert to the relentless demands of the sea as she works the vessel with forces beyond measure. A watchful eye on deck and aloft will detect an unfair lead, a fouled line or a chafing sail before the dreaded sound of shredding cloth tells you it’s too late. Keen observation of the sea and sky can keep you clear of a waterspout by day or merchant ship at night.

By the third day at sea our routine was second nature and more activities filled our hours. We took sun, moon and star sights with the trusty old sextant that has guided me across the ocean for 45 years. GPS may be more accurate, but when the screen goes blank or the batteries die, the sextant will never fail you. From the galley a stream of gastronomical achievements were delivered by our collection of accomplished sea cooks with welcome regularity. We were well provisioned with locally grown Vineyard produce, and rarely was there something delectable not bubbling and squeaking on the galley stove to nourish five ravenous bodies.

We approached Bermuda in fair weather and light air and sailed through the cut to St. Georges harbor on December 2, 2014— four days after our frigid departure from Vineyard Haven. We had completed the first leg of our voyage with all hands in fine form and the schooner CHARLOTTE at her best. With our American ensign flying from the taffrail, and the Bermuda courtesy flag above the “Q” (quarantine) flag at the starboard foremast spreader, we came alongside the customs dock for clearance.

The schooner rig evolved during the 18th and 19th centuries and became very popular for its relative ease of handling by a small crew. These working vessels were used for fishing and carrying cargo, coastwise as well as offshore. They were known for their good turn of speed, ability to windward, and their seaworthiness. The early racing yachts such as the legendary AMERICA were schooner rigged, and in recent years the schooner has been rediscovered by yacht designers for its desirable characteristics as a cruising boat.

The larger the vessel, the more sail is required to drive its heavier hull through the water. By dividing up the sail area into smaller pieces spread out upon two masts, the easier each sail is to set, trim and lower. Although there are more strings to pull than on a boat with only one mast (a sloop or a cutter) there are also more options in sail combinations. I designed CHARLOTTE to fit a job description that ranges from a family boat capable of cruising with as many as ten close relatives onboard, day sailing with a dozen or more friends, chartering with six guests having no sailing experience among them, as well as ocean sailing to distant ports. Compromise is the one constant in yacht design, and CHARLOTTE has met her multifaceted purpose mission with high marks. She is a low tech, semi-gloss comfortable creature that sails easily and works well for us. She’s also easy on the helm and pleasant to the eye.

The courteous welcome from the Bermudian customs officials set the tone for our reception in this lonely mid-Atlantic volcanic archipelago that’s surrounded by a pale turquoise sea lapping at pink white sand or colliding against rugged rock-faced bluffs and nourishing the thriving coral terrace. We set off on a hike to stretch our legs and soak up the rich variety of color and aroma along the trails of this gardener’s paradise. Meandering out to the Fort that once protected the harbor entrance, we looked out to sea and reflected on the stunning change from the winter landscape we had left only four days ago. Voyaging under sail was man’s earliest method of discovering new lands, and such adventure stirs one’s primordial foundation like a lost prehistoric memory rekindled.

Our bus and ferry ride to The Dockyard Museum brought home the historical significance of this colorful pastel outpost. Dockyard is a major fortification constructed by the British shortly after their embarrassing defeat by a hardscrabble collection of American colonial rebels in the war of independence. Desperately in need of a military presence in the western Atlantic, the once indominatable Brits resolved to construct an ingenious fortification and naval base out of locally-cut stone. A masterpiece of architectural and engineering expertise, regretfully, it was built at the expense of countless Bermudian lives subjected to the appalling cruelty and inhuman labor and living conditions employed by the masters of war. This recently-restored impenetrable rockbound bulwark will soon be the center stage for another battle named for the victorious schooner AMERICA in 1851: the America’s Cup. This yacht race between captains of industry is slated for 2017 in the windy environs of Dockyard.

After a flurry of provisioning and filling tanks, and of Brad replacing a water pump and a thorough check of the rig, engine and ships gear, we said farewell to sailmakers Stevie and Suzanne Hollis, our dear old friends and the main reason for our visit to this secluded emerald jewel in the western ocean. We were all eager to get underway again and ride the North Atlantic another 1,100 nautical miles south to our winter home, Haiti. It felt good to be back in our sea-rolling world, standing watch with our pals—five bonded boys in a boat.

A fair wind from the north, bolstered by a steep confused sea, kept the helmsman alert and some appetites reduced as CHARLOTTE boiled along, ticking off the miles day after day. We became reacquainted with the night sky overflowing with stars and observed the wonders above in the coolness of the tropical darkness. For every 60 nautical miles gained on our southerly course, Polaris (the North Star) slid down towards the horizon astern one degree in altitude, mimicking our change in latitude. On rare occasions, a ship would appear on the horizon and the watch captain would take a bearing to determine its course. If your bearing doesn’t change, it’s a collision situation and time to alter your heading. Constant vigilance!

The dawn watch is my favorite, if only for the relief of light following darkness, which in foul weather can be very nerve racking. After a long and harrowing visionless night watch, a welcome sunrise restores your ability to observe the ship and see how this complex contraption of lumber, line, bronze and canvas has survived the thrashing and pitching in blindness—as if she needs to see. Those lucky souls who enjoy the rosy fingers of early-morning sunshine are also expected to conduct a general cleanup aboard: washing down the cockpit, sweeping up below deck, organizing the galley and any other tasks required to keep the vessel shipshape.

The traditional midday ritual of calculating our position with a noontime sight got everyone on deck estimating the previous 24 hour days run. We had some good ones, the best one logging just over 200 nautical miles—an average speed of 8 knots.

At sunset we strained our eyes in search of the “green flash,” the visual phenomenon that rarely occurs just as the upper limb of the sun touches the horizon before sinking beneath the sea. No flash on this voyage, but stunning pre-prandial entertainment with the evening sky exploding with colors and composition that painters can only wish for. The divine fish guardians were clearly in control of our yellow and pink feathered lures trolling astern, fouling the hooks with Sargasso weed and protecting the scaly creatures from our baking dish. No fresh barracuda, wahoo or bonito on this passage, just a comforting sense of our ecological commitment in mitigating the catastrophic overfishing of the world’s oceans as we sank our forks into another bowl of rice and beans, yet again. Hot sauce, anyone?

You can CLICK HERE to read Part 2, and see Haiti through Nat’s eyes.

Greg Stamatelakys says:

I do believe the 18th paragraph starting with the words ‘Rest assured’ is pure writer’s gold.

Thank you to the vessel’s owners for making a noble voyage of discovery and assistance.

Baxter Gillespie says:

Awesome story and photos! Thanks Nat and OCH.

Peter Beckett says:

A great story and a great boat Nat. Just a comment about your sojourn in Bermuda to put facts right. I don’t think you will find that any Bermudians lost their lives building the dockyard at the western end of our island. They shipped out prisoners from the UK who lived on hulks in inhumane conditions in order to get the job done for the British navy and many of them were to perish under the harsh treatment meted out.

William English says:

Wonderfully written! Looking forward to your sail to Haiti. Now I’ll look up “Ile a Vache”. Sounds like a bit of paradise in a country of extremely poor, but wonderfully optimistic people.

Edwin Spears says:

I Love it!

Matthew Peterson says:

What an absolutely stunning boat and a brilliant voyage.

I’m building a Don Kurylko Alaska Lug Ketch right now but this timber boat thing runs deep. Very deep.

Thanks for sharing your journey !!!

Matt from Blue Mountains, Australia

Conbert Benneck says:

William, you need a tender in order to get ashore when you are anchored in a harbor. A life raft has a canopy over the top to protect you from the sun. It is a survival vessel and you can’t just row it ashore to pick up provisions. So, you need both on an ocean going vessel.

Stephen McClure says:

An engrossing nautical adventure well told. Looking forward to Part 2.

William Hammond says:

Excellent reading! Being a novice to sailing I’m curious as to why you have both a Tender and a Life Raft? Space considerations would seem to dictate one but not both. I’m looking forward to Part 2.

Andy Reynolds says:

William, a tender is for transporting crew and gear from ship to shore, or another vessel, and can be directed with oars and/or motor or sail, for everyday usage, at least if anchoring or in a port. A liferaft is for emergency use in an abandon ship situation, and usually has no provision for direction or power, it drifts. Its purpose is to keep the crew alive long enough to be rescued. Both are essential for offshore sailing, and even for coastal cruising, a good idea.

Fred Murphy says:

It was fun reading Part 1. Obviously writing is another one of your virtues!

Mark Pellerin says:

BRAVO. I love this …but tear-up thinking of Haiti’s lovely people. I sailed down from MD via the Bahamas in ’77 and then again in ’79. The scenery is as described and I suspect that the country is no better with continued ruinous government and an earthquake !

Raymond Morgan says:

Nat, your colorful and wonderful story makes a compelling reason for quoting your job, building a boat, and sailing away. Thank you, Thank you. OCH is a national treasure to be enjoyed by all. Keep up the great work.

Morgan

Ellen Massey Leonard says:

What a wonderful voyage, boat, and narrative! Looking forward to Part 2!

Judie Romeo says:

Your words paint some compelling images Nat. I was hot, I was cold. I drooled as I smelled those delectable aromas coming from the stewpot. And I learned what a katabatic wind is. Can’t wait to see part 2. Thanks for letting us all join your virtual crew.

Weaver Lilley says:

What a great adventure. I feel like I’m there on the boat.