Among the dockside pundits, the discussion of light vs. heavy displacement usually revolves around the ability of a cruising sailboat to carry the necessary provisions and gear for extended cruising. I would like to consider the question from another angle: appearance and cost.

Light displacement boats have some real advantages. Up to a certain point, lighter displacement saves money, both in initial cost and continuing expenses. Cy Hamlin pioneered this idea with his Controversy yachts produced at Mt. Desert Yacht Yard in the 1960s. Many people are surprised to learn that boats, like meat, tend to cost by the pound, not the foot. Compared to a heavy displacement 40-foot sailboat, a lighter boat of the same length will require smaller sails, lighter rigging, smaller ground tackle, a smaller engine, and less ballast.

Under many conditions, lighter boats can also be faster. For one thing, they can cheat the devil of hull speed, even plane if they are very light and have the proper hull shape. This was one reason that MARY ANN, the first Barnegat Bay A Cat, was able to sweep aside the older heavier competition on the bay, even though they sported vastly bigger sail plans.

Nat Herreshoff, the Wizard of Bristol, took advantage of both of these factors. One of the many facets of his wizardliness was his intuitive feel for light, stiff and strong construction. His boats generally had lighter structure than the competition, making them both cheaper to build and faster under sail. Even when a rating rule demanded that boats be of a certain displacement, lighter construction meant that more of that weight could be put into ballast. Ballast is not only one of the cheapest components per pound in a boat, but a greater proportion of ballast increases stability, meaning that the boat can stand up to more wind before reefing.

Aesthetics, however, is one area where lighter boats have trouble competing. While they may not be able to enumerate the reasons, most people will admit that older boats tend to look more graceful and appealing than their modern sisters. Although several factors are involved, a major one is freeboard, or the amount of hull that shows above the waterline. Older boats generally have less, and just as with cars, lower and sleeker usually looks better.

In the world of boat design numbers (called hydrostatics), the relative “lightness” or “heaviness” of a boat is defined by its displacement/length ratio, usually abbreviated as D/L. I’ll spare you the formula, but keep in mind that this is a dimensionless number – in other words, it makes no difference if the boat is a dinghy or an ocean liner. If her D/L is 400 she is considered to be in the heavy displacement realm. If the D/L is 150, she is pretty light.

Why do lighter boats tend to be higher sided? Archimedes who purportedly jumped out of his tub and ran naked through the streets of ancient Syracuse shouting “Eureka!” is credited with the answer. The heavier a boat is, the more there is of it under water. The more there is under water, the less of it there needs to be above water to get the same amount of headroom.

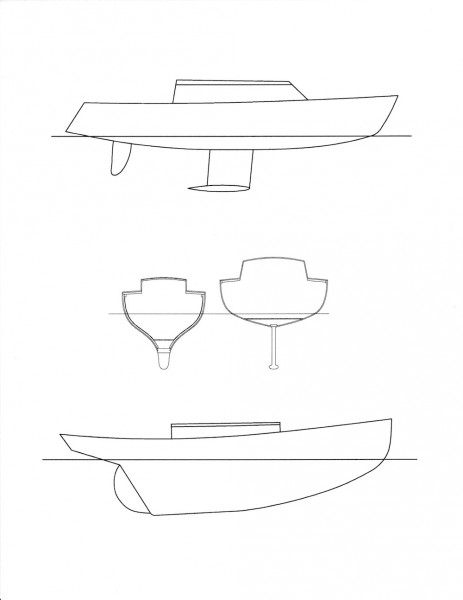

Consider the two boats shown below, one an old style heavy cruiser (D/L 400), the other a modern light displacement sister (D/L 150). Both boats have an overall length of 33′, a waterline length of 28 feet and a draft of 5 1/2 feet. They both have the same 6-foot headroom, but the cabin sole of the lighter boat must be much higher, so either the topsides or the cabin (usually both) has to be moved up to get the same headroom.

So, tall people who are unwilling to bump their heads (or bend over to avoid it) can be the ruination of good looks in small, light displacement boats. Daysailers, where headroom is not considered essential, are generally immune to this problem, and once a yacht gets to 60 or so feet in length, there is plenty of height in either type for homo erects.

. . . sign up to the right to get immediate access to this full post,

plus you'll get 10 of our best videos for free.

Get Free Videos& Learn More Join Now!!for Full Access Members Sign In

Paul Rybon says:

One of the most puzzling riddles is with the incessant pitching of my Wittholtz designed Dickerson 35 ketch. Hull specs and profiles are online. The other annoyance is with the ultra-quick movement unless hard-pressed with sail. Also, even in small-to-moderate waves, it comes to almost a complete stop upon meeting a wave. So here’s my question; I’m about to replace the bottom because the seams and frames are worn out. Do you think the boat would have better riding characteristics if I widened it at the same time? Should I add more ballast? Spread out the ballast? Lower the sides? Instal heavier masts? Mr. W. is gone, can’t ask him. Any ideas? Paul on the Chesapeake Bay

Charles Zimmermann says:

It would be great to see this blog continued regarding the difference in sea keeping, movement through the waves, interior livability, and aesthetics – with a focus on sailors who are over 50 years old and simply want to sail down the coast and maybe reach Martha’s Vineyard if the winds are favorable, or maybe just spend a night in Provincetown if the winds are not. In other words, a focus on the kind of cruising in which two to four people could get out on the water and have fond memories when they get back to the boat’s home port.

Also I’d like to add a comment on headroom. I am 6 feet 2 and I couldn’t possibly afford a 60 foot boat; I have a heavy displacement traditionally built 30 foot boat which was custom built for someone about 4 inches shorter. Every time I hit my head I wish he had been a little taller.

William Lavender says:

With your experience with Quiet Tune, how do you think Joel White reconciled these factors in his adaptation of this design?

Doug Hylan says:

QUIET TUNE is pretty light, something LFH, who by this time was abandoning any concern for rating rules, achieved by lengthening the waterline (reducing overhangs). In fact the displacement length ratio for the two boats is for all intent and purposes, the same (222 for GRACE, the first CH 31, and 231 for QUIET TUNE). GRACE is 1 1/2 feet longer and has about 4″ more freeboard. Both boats have about 50″ of headroom: Joel could match the headroom number (about the minimum necessary for sitting headroom) through the 31’s bigger size, higher freeboard and beamless cabin top. Most of the subsequent Center Harbor 31s had their sheer raised 3″.

Cold molded construction and a lighter rig allowed Joel to put a bit more of that displacement into ballast, but QT is no slouch in the ballast ratio department. But QT is badly under rigged, and Joel, who by that time had embraced computer aided stability calculations, was able to confidently correct that situation.

In fact, I don’t believe that the Center Harbor 31s owe very much to the QUIET TUNE design. Yes, they are both daysailers of essentially the same size. But as much as any boat can be considered an original design after several centuries of precedent, the CH 31’s are pure White, much more an evolutionary step in Joel’s work than an adaption of LFH’s.

William Lavender says:

Thanks Doug! I’ve always loved Quiet Tune’s lines (She’s my “Someday I’ll build that…” boat) and I appreciate any chance to learn more about her. Love your video by the way.

This is a great article and I too hope to read more about the details of displacement!

Steve Stone says:

Thanks Doug… a picture’s worth a 1000 words. Intelligent analysis of two contrasting images side by side… priceless. It cleared up the “why?” about modern boats’ tendency toward high freeboard, and perhaps part of the logic behind straight sheers as well (for, among other things, more standing headroom amidships?). This brought home the point more clearly than I’ve seen before.

Paul Rybon says:

Sounds good, so far. How about a ‘page 2?’

Benjamin Mendlowitz says:

Thanks Doug, this is a really informative discussion in clear simple language. I would love to see it continued regarding the differences in sea keeping, movement through the waves, interior livability and aesthetics.

Doug Hylan says:

When Robin Knox-Johnson rounded the world in SUHAILI in 1969, he did it in the type of boat that was considered best suited for roaring forties sailing at the time — a very heavy double ended ketch. At that time it would have been considered suicidal to go very far out of sight of land in the type of boats that now regularly complete this race. These ultra light sloops with huge open sterns never heave to. The harder it blows, the faster they sail! Although I doubt that comfort at sea plays a very big part in these sailors’ decisions about what type of design they should use, clearly the boats, if properly handled, can handle horrific weather, and I doubt that their voyages could be much less comfortable than Knox-Johnson’s.

Charles Barclay says:

It’s also been described as “shortening the period of discomfiture”.